|

Lucas Ballard

|

Seny Kamara

|

Michael K. Reiter

|

The inability of humans to generate and remember strong secrets makes it difficult for people to manage cryptographic keys. To address this problem, numerous proposals have been suggested to enable a human to repeatably generate a cryptographic key from her biometrics, where the strength of the key rests on the assumption that the measured biometrics have high entropy across the population. In this paper we show that, despite the fact that several researchers have examined the security of BKGs, the common techniques used to argue the security of practical systems are lacking. To address this issue we reexamine two well known, yet sometimes misunderstood, security requirements. We also present another that we believe has not received adequate attention in the literature, but is essential for practical biometric key generators. To demonstrate that each requirement has significant importance, we analyze three published schemes, and point out deficiencies in each. For example, in one case we show that failing to meet a requirement results in a construction where an attacker has a 22% chance of finding ostensibly 43-bit keys on her first guess. In another we show how an attacker who compromises a user's cryptographic key can then infer that user's biometric, thus revealing any other key generated using that biometric. We hope that by examining the pitfalls that occur continuously in the literature, we enable researchers and practitioners to more accurately analyze proposed constructions.

While cryptographic applications vary widely in terms of assumptions, constructions, and goals, all require cryptographic keys. In cases where a computer should not be trusted to protect cryptographic keys--as in laptop file encryption, where keeping the key on the laptop obviates the utility of the file encryption--the key must be input by its human operator. It is well known, however, that humans have difficulty choosing and remembering strong secrets (e.g., [2,14]). As a result, researchers have devoted significant effort to finding input that has sufficient unpredictability to be used in cryptographic applications, but that remains easy for humans to regenerate reliably. One of the more promising suggestions in this direction are biometrics--characteristics of human physiology or behavior. Biometrics are attractive as a means for key generation as they are easily reproducible by the legitimate user, yet potentially difficult for an adversary to guess.

There have been numerous proposals for generating cryptographic keys from biometrics (e.g., [33,34,28]). At a high level, these Biometric Cryptographic Key Generators, or BKGs, follow a similar design: during an enrollment phase, biometric samples from a user are collected; statistical functions, or features, are applied to the samples; and some representation of the output of these features is stored in a data structure called a biometric template. Later, the same user can present another sample, which is processed with the stored template to reproduce a key. A different user, however, should be unable to produce that key. Since the template itself is generally stored where the key is used (e.g., in a laptop file encryption application, on the laptop), a template must not leak any information about the key that it is used to reconstruct. That is, the threat model admits the capture of the template by the adversary; otherwise the template could be the cryptographic key itself, and biometrics would not be needed to reconstruct the key at all.

Generally, one measures the strength of a cryptographic key by its

entropy, which quantifies the amount of uncertainty in the key

from an adversary's point of view. If one regards a key generator as

drawing an element uniformly at random from a large set, then the

entropy of the keys can be easily computed as the base-two logarithm

of the size of the set. Computing the entropy of keys output by a

concrete instantiation of a key generator, however, is non-trivial

because "choosing uniformly at random" is difficult to achieve in

practice. This is in part due to the fact that the key generator's

source of randomness may be based on information that is leaked by

external sources. For instance, an oft-cited flaw in Kerberos version

4 allowed adversaries to guess ostensibly 56-bit DES session keys in

only ![]() guesses [13]. The problem stemmed from the fact

that the seeding information input to the key generator was related to

information that could be easily inferred by an adversary. In other

words, this auxiliary information greatly reduced the entropy of

the key space.

guesses [13]. The problem stemmed from the fact

that the seeding information input to the key generator was related to

information that could be easily inferred by an adversary. In other

words, this auxiliary information greatly reduced the entropy of

the key space.

In the case of biometric key generators, where the randomness used to generate the keys comes from a user's biometric and is a function of the particular features used by the system, the aforementioned problems are compounded by several factors. For instance, in the case of certain biometric modalities, it is known that population statistics can be strong indicators of a specific user's biometric [10,36,3]. In other words, depending on the type of biometric and the set of features used by the BKG, access to population statistics can greatly reduce the entropy of a user's biometric, and consequently, reduce the entropy of her key. Moreover, templates could also leak information about the key. To complicate matters, in the context of biometric key generation, in addition to evaluating the strength of the key, one must also consider the privacy implications associated with using biometrics. Indeed, the protection of a user's biometric information is crucial, not only to preserve privacy, but also to enable that user to reuse the biometric key generator to manage a new key. We argue that this concern for privacy mandates not only that the template protect the biometric, but also that the keys output by a BKG not leak information about the biometric. Otherwise, the compromise of a key might render the user's biometric unusable for key generation thereafter.

The goal of this work is to distill the seemingly intertwined and complex security requirements of biometric key generators into a small set of requirements that facilitate practical security analyses by designers.

Specifically, the contributions of this paper are:

Throughout this paper we focus on the importance of considering adversaries who have access to public information, such as templates, when performing security evaluations. We hope that our observations will promote critical analyses of BKGs and temper the spread of flawed (or incorrectly evaluated) proposals.

To our knowledge, Soutar and Tomko [34] were the first to propose biometric key generation. Davida et al. [9] proposed an approach that uses iris codes, which are believed to have the highest entropy of all commonly-used biometrics. However, iris code collection can be considered somewhat invasive and the use of majority-decoding for error correction--a central ingredient of the Davida et al. approach--has been argued to have limited use in practice [16].

Monrose et al. proposed the first practical system that exploits

behavioral (versus physiological) biometrics for key

generation [29]. Their technique uses keystroke latencies to

increase the entropy of standard passwords. Their construction yields

a key at least as secure as the password alone, and an empirical

analysis showed that in some instances their approach increases the

workload of an attacker by a multiplicative factor of ![]() .

Later, a similar approach was used to generate cryptographic keys from

voice [28,27]. Many constructions followed those of

Monrose et al., using biometrics such as face [15],

fingerprints [33,39], handwriting [40,17] and

iris codes [16,45]. Unfortunately, many are susceptible to

attacks. Hill-climbing attacks have been leveraged against

fingerprint, face, and handwriting-based biometric

systems [1,37,43] by exploiting information leaked

during the reconstruction of the key from the biometric template.

.

Later, a similar approach was used to generate cryptographic keys from

voice [28,27]. Many constructions followed those of

Monrose et al., using biometrics such as face [15],

fingerprints [33,39], handwriting [40,17] and

iris codes [16,45]. Unfortunately, many are susceptible to

attacks. Hill-climbing attacks have been leveraged against

fingerprint, face, and handwriting-based biometric

systems [1,37,43] by exploiting information leaked

during the reconstruction of the key from the biometric template.

There has also been an emergence of generative attacks against biometrics [5,23], which use auxiliary information such as population statistics along with limited information about a target user's biometric. The attacks we present in this paper are different from generative attacks because we assume that adversaries only have access to templates and auxiliary information. Our attacks, therefore, capture much more limited, and arguably more realistic, adversaries. Despite such limited information, we show how an attacker can recover a target user's key with high likelihood.

There has also been recent theoretical work to formalize particular aspects of biometric key generators. The idea of fuzzy cryptography was first introduced by Juels and Wattenberg [21], who describe a commitment scheme that supports noise-tolerant decommitments. In Section 7 we provide a concrete analysis of a published construction that highlights the pitfalls of using fuzzy commitments as biometric key generators. Further work included a fuzzy vault [20], which was later analyzed as an instance of a secure-sketch that can be used to build fuzzy extractors [11,6,12,22]. Fuzzy extractors treat biometric features as non-uniformly distributed, error-prone sources and apply error-correction algorithms and randomness extractors [18,30] to generate random strings.

Fuzzy cryptography has made important contributions by specifying formal security definitions with which BKGs can be analyzed. Nevertheless, there remains a gap between theoretical soundness and practical systems. For instance, while fuzzy extractors can be effectively used as a component in a larger biometric key generation system, they do not capture all the practical requirements of a BKG. In particular, it is unclear whether known constructions can correct the kinds of errors typically generated by humans, especially in the case of behavioral biometrics. Moreover, fuzzy extractors require biometric inputs with high min-entropy but do not address how to select features that achieve this requisite level of entropy. Since this is an inherently empirical question, much of our work is concerned with how to experimentally evaluate the entropy available in a biometric.

Lastly, Jain et al. enumerate possible attacks against biometric templates and discuss several practical approaches that increase template security [19]. Similarly, Mansfield and Wayman discuss a set of best practices that may be used to measure the security and usability of biometric systems [24]. While these works describe specific attacks and defenses against systems, they do not address biometric key generators and the unique requirements they demand.

Before we can argue about how to accurately assess biometric key generators (BKGs), we first define the algorithms and components associated with a BKG. These definitions are general enough to encompass most proposed BKGs.

BKGs are generally composed of two algorithms, an enrollment algorithm

(

![]() ) and a key-generation algorithm (

) and a key-generation algorithm (

![]() ):

):

The enrollment algorithm estimates the variation inherent to a

particular user's biometric reading and computes information needed

to error-correct a new sample that is sufficiently close to the

enrollment samples.

![]() encodes this information into a template and

outputs the template and the associated key. The key-generation

algorithm uses the template output by the enrollment algorithm and a

new biometric sample to output a key. If the provided sample is

sufficiently similar to those provided during enrollment, then

encodes this information into a template and

outputs the template and the associated key. The key-generation

algorithm uses the template output by the enrollment algorithm and a

new biometric sample to output a key. If the provided sample is

sufficiently similar to those provided during enrollment, then

![]() and

and

![]() output the same keys.

output the same keys.

Generally speaking, there are four classes of information associated with a BKG.

For the remainder of the paper if a component of a BKG is associated

with a specific user, then we subscript the information with the

user's unique identifier. So, for example,

![]() , is

, is

![]() 's biometric and

's biometric and

![]() is auxiliary information

derived from all users

is auxiliary information

derived from all users ![]() .

.

In the context of biometric key generation, security is not as easily defined as correctness. Loosely speaking, a secure BKG outputs a key that "looks random" to any adversary that cannot guess the biometric. In addition, the templates and keys derived by the BKG should not leak any information about the biometric that was used to create them. We enumerate a set of three security requirements for biometric key generators, and examine the components that should be analyzed mathematically (i.e., the template and key) and empirically (i.e., the biometric and auxiliary information). While the necessity of the first two requirements has been understood to some degree, we will highlight and analyze how previous evaluations of these requirements are lacking. Additionally, we discuss a requirement that is often overlooked in the practical literature, but one which we believe is necessary for a secure and practical BKG.

We consider a BKG secure if it meets the following three requirements for each enrollable user in a population:

The necessity of

![]() and

and

![]() is well known, and indeed many

proposals make some sort of effort to argue security along these

lines (see, e.g., [29,11]). However, many different

approaches are used to make these arguments. Some take a

cryptographically formal approach, whereas others provide an empirical

evaluation aimed at demonstrating that the biometrics and the

generated keys have high entropy. Unfortunately, the level of rigor

can vary between works, and differences in the ways

is well known, and indeed many

proposals make some sort of effort to argue security along these

lines (see, e.g., [29,11]). However, many different

approaches are used to make these arguments. Some take a

cryptographically formal approach, whereas others provide an empirical

evaluation aimed at demonstrating that the biometrics and the

generated keys have high entropy. Unfortunately, the level of rigor

can vary between works, and differences in the ways

![]() and

and

![]() are typically argued make it difficult to compare

approaches. Also, it is not always clear that the empirical

assumptions required by the cryptographic algorithms of the BKG can be met in

practice.

are typically argued make it difficult to compare

approaches. Also, it is not always clear that the empirical

assumptions required by the cryptographic algorithms of the BKG can be met in

practice.

Even more problematic is that many approaches for demonstrating biometric security merely provide some sort of measure of entropy of a biometric (or key) based on variation across a population. For example, one common approach is to compute biometric features for each user in a population, and compute the entropy over the output of these features. However, such analyses are generally lacking on two counts. For one, if the correlation between features is not accounted for, the reported entropy of the scheme being evaluated could be much higher than what an adversary must overcome in practice. Second, such techniques fail to compute entropy as a function of the biometric templates, which we argue should be assumed to be publicly available. Consequently, such calculations would declare a BKG "secure" even if, say, the template leaked information about the derived key. For example, suppose that a BKG uses only one feature and simply quantizes the feature space, outputting as a key the region of the feature space that contains the majority of the measurements of a specific user's feature. The quantization is likely to vary between users, and so the partitioning information would need to be stored in each user's template. Possession of the template thus reduces the set of possible keys, as it defines how the feature space is partitioned.

As far as we know, the notion of Strong Biometric Privacy (

![]() )

has only been considered recently, and only in a theoretical

setting [12]. Even the original definitions of fuzzy

extractors [11, Definition 3] do not explicitly address this

requirement. Unfortunately,

)

has only been considered recently, and only in a theoretical

setting [12]. Even the original definitions of fuzzy

extractors [11, Definition 3] do not explicitly address this

requirement. Unfortunately,

![]() has also largely been ignored

by the designers of practical systems. Perhaps this oversight is due

to lack of perceived practical motivation--it is not immediately

clear that a key could be used to reveal a user's biometric. Indeed,

to our knowledge, there have been few, if any, concrete attacks that

have used keys and templates to infer a user's biometric. We observe,

however, that it is precisely practical situations that motivate such

a requirement; keys output by a BKG could be revealed for any number

of reasons in real systems (e.g., side-channel attacks against

encryption keys, or the verification of a MAC). If a key can be used

to derive the biometric that was used to generate the key, then key

recovery poses a severe privacy concern. Moreover, key compromise

would then preclude a user from using this biometric in a BKG ever

again, as the adversary would be able to recreate any key the user

makes thereafter. Therefore, in Section 7 we provide

specific practical motivation for this requirement by describing an

attack against a well-accepted BKG. The attack combines the key and a

template to infer a user's biometric.

has also largely been ignored

by the designers of practical systems. Perhaps this oversight is due

to lack of perceived practical motivation--it is not immediately

clear that a key could be used to reveal a user's biometric. Indeed,

to our knowledge, there have been few, if any, concrete attacks that

have used keys and templates to infer a user's biometric. We observe,

however, that it is precisely practical situations that motivate such

a requirement; keys output by a BKG could be revealed for any number

of reasons in real systems (e.g., side-channel attacks against

encryption keys, or the verification of a MAC). If a key can be used

to derive the biometric that was used to generate the key, then key

recovery poses a severe privacy concern. Moreover, key compromise

would then preclude a user from using this biometric in a BKG ever

again, as the adversary would be able to recreate any key the user

makes thereafter. Therefore, in Section 7 we provide

specific practical motivation for this requirement by describing an

attack against a well-accepted BKG. The attack combines the key and a

template to infer a user's biometric.

In what follows, we provide practical motivation for the importance of each of our three requirements by analyzing three published BKGs. It is not our goal to fault specific constructions, but instead to critique evaluation techniques that have become standard practice in the field. We chose to analyze these specific BKGs because each was argued to be secure using "standard" techniques. However, we show that since these techniques do not address important requirements, each of these constructions exhibit significant weaknesses despite security arguments to the contrary.

Before continuing further, we note that analyzing the security of a biometric key generator is a challenging task. A comprehensive approach to biometric security should consider sources of auxiliary information, as well as the impact of human forgers. Though it may seem impractical to consider the latter as a potential threat to a standard key generator, skilled humans can be used to generate initial forgeries that an algorithmic approach can then leverage to undermine the security of the BKG.

To this point, research has accepted this "adversarial multiplicity" without examining the consequences in great detail. Many works (e.g., [33,29,17,15,40,16]) report both False Accept Rates (i.e., how often a human can forge a biometric) and an estimate of key entropy (i.e., the supposed difficulty an algorithm must overcome in order to guess a key) without specifically identifying the intended adversary. In this work, we focus on algorithmic adversaries given their importance in offline guessing attacks, and because we have already addressed the importance of considering human-aided forgeries [4,5]. While our previous work did not address biometric key generators specifically, those lessons apply equally to this case.

The security of biometric key generators in the face of algorithmic adversaries

has been argued in several different ways, and each approach has advantages

and disadvantages. Theoretical approaches (e.g., [11,6]) begin by

assuming that the biometrics have high adversarial min-entropy (i.e.,

conditioned on all the auxiliary information available to an adversary, the

entropy of the biometric is still high) and then proceed to distill this entropy

into a key that is statistically close to uniform. However, in practice, it is

not always clear how to estimate the uncertainty of a biometric. In

more practical settings, guessing entropy [25] has been

used to measure the strength of keys (e.g., [29,27,10]), as it

is easily computed from empirical data. Unfortunately, as we demonstrate

shortly, guessing entropy is a summary statistic and can thus yield misleading

results when computed over skewed distributions. Yet another common approach

(e.g., [31,7,16,41,17]), which has lead to somewhat

misleading views on security, is to argue key strength by computing the Shannon entropy

of the key distribution over a population.

More precisely, if we consider a BKG that assigns the key

![]() to a user

to a user ![]() in a population

in a population ![]() , then it is considered "secure" if the entropy of the

distribution

, then it is considered "secure" if the entropy of the

distribution

![]() is high. We note,

however, that the entropy of the previous distribution measures only

key uniqueness and says nothing about how difficult it is for an adversary to

guess the key. In fact, it is not difficult to design BKGs that output keys with

maximum entropy in the previous sense, but whose keys are easy for an

adversary to guess; setting

is high. We note,

however, that the entropy of the previous distribution measures only

key uniqueness and says nothing about how difficult it is for an adversary to

guess the key. In fact, it is not difficult to design BKGs that output keys with

maximum entropy in the previous sense, but whose keys are easy for an

adversary to guess; setting

![]() is a trivial example.

is a trivial example.

To address these issues, we present a new measure that is easy to compute empirically and that estimates the difficulty an adversary will have in guessing the output of a distribution given some related auxiliary distribution. It can be used to empirically estimate the entropy of a biometric for any adversary that assumes the biometric is distributed similarly to the auxiliary distribution. Our proposition, Guessing Distance, involves determining the number of guesses that an adversary must make to identify a biometric or key, and how the number of guesses are reduced in light of various forms of auxiliary information.

We assume that a specific user ![]() induces a distribution

induces a distribution

![]() over a

finite,

over a

finite, ![]() -element set

-element set ![]() . We also assume that an adversary

has access to population statistics that also induce a distribution,

. We also assume that an adversary

has access to population statistics that also induce a distribution,

![]() , over

, over ![]() .

. ![]() could be computed from the distributions of

other users

could be computed from the distributions of

other users ![]() . We seek to quantify how useful

. We seek to quantify how useful ![]() is at

predicting

is at

predicting

![]() . The specification of

. The specification of ![]() varies depending on

the BKG being analyzed;

varies depending on

the BKG being analyzed; ![]() could be a set of biometrics, a set

of possible feature outputs, or a set of keys. It is up to system

designers to use the specification of

could be a set of biometrics, a set

of possible feature outputs, or a set of keys. It is up to system

designers to use the specification of ![]() that would most likely

be used by an adversary. For instance, if the output of features are

easier to guess than a biometric, then

that would most likely

be used by an adversary. For instance, if the output of features are

easier to guess than a biometric, then ![]() should be defined as

the set of possible feature outputs. Although at this point we keep

the definition of

should be defined as

the set of possible feature outputs. Although at this point we keep

the definition of ![]() and

and

![]() abstract, it is important when

assessing the security of a construction to take as much auxiliary

information as possible into account when estimating

abstract, it is important when

assessing the security of a construction to take as much auxiliary

information as possible into account when estimating ![]() . We return

in Section 5 with an example of such an analysis.

. We return

in Section 5 with an example of such an analysis.

We desire a measure that estimates the number of guesses that an

adversary will make to find the high-probability elements of

![]() ,

when guessing by enumerating

,

when guessing by enumerating ![]() starting with the most likely

elements as prescribed by

starting with the most likely

elements as prescribed by ![]() . That is, our measure need not

precisely capture the distance between

. That is, our measure need not

precisely capture the distance between

![]() and

and ![]() (as might, say,

(as might, say,

![]() -distance or Relative Entropy), but rather must capture simply

-distance or Relative Entropy), but rather must capture simply

![]() 's ability to predict the most likely elements as described by

's ability to predict the most likely elements as described by

![]() 1. Given a user's distribution

1. Given a user's distribution

![]() , and

two (potentially different) population distributions

, and

two (potentially different) population distributions ![]() and

and

![]() , we would like the distance between

, we would like the distance between

![]() and

and ![]() and

and

![]() and

and ![]() to be the same if and only if

to be the same if and only if ![]() and

and ![]() prescribe

the same guessing strategy for a random variable distributed according

to

prescribe

the same guessing strategy for a random variable distributed according

to

![]() . For example, consider the distributions

. For example, consider the distributions

![]() ,

, ![]() and

and

![]() , and the element

, and the element

![]() such that

such that

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() . Here, an adversary

with access to

. Here, an adversary

with access to ![]() would require the same number of guesses to find

would require the same number of guesses to find

![]() as an adversary with access to

as an adversary with access to ![]() (one). Thus, we would

like the distance between

(one). Thus, we would

like the distance between

![]() and

and ![]() and between

and between

![]() and

and ![]() to be the same.

to be the same.

Guessing Distance measures the number of guesses that an adversary who

assumes that

![]() makes before guessing the most likely

element as prescribed by

makes before guessing the most likely

element as prescribed by

![]() (that is,

(that is, ![]() )2. We take

the average over

)2. We take

the average over ![]() and

and ![]() as it may be the case that several

elements may have similar probability masses under

as it may be the case that several

elements may have similar probability masses under ![]() . In such a

situation, the ordering of

. In such a

situation, the ordering of ![]() may be ambiguous, so we report an

average measure across all equivalent orderings. As

may be ambiguous, so we report an

average measure across all equivalent orderings. As

![]() and

and ![]() will typically be empirical estimates, we use a tolerance

will typically be empirical estimates, we use a tolerance ![]() to

offset small measurement errors when grouping elements of similar

probability masses. The subscript

to

offset small measurement errors when grouping elements of similar

probability masses. The subscript ![]() is ignored if

is ignored if

![]() .

.

An important characteristic of

![]() is that it compares two

probability distributions. This allows for a more fine-tuned

evaluation as one can compute

is that it compares two

probability distributions. This allows for a more fine-tuned

evaluation as one can compute

![]() for each user in the

population. To see the overall strength of a proposed approach, one

might report a CDF of the

for each user in the

population. To see the overall strength of a proposed approach, one

might report a CDF of the

![]() 's for each user, or report the

minimum over all

's for each user, or report the

minimum over all

![]() 's in the population.

's in the population.

Guessing Distance is superficially similar to Guessing Entropy [25], which is commonly used to compute the expected number of guesses it takes to find an average element in a set assuming an optimal guessing strategy (i.e., first guessing the element with the highest likelihood, followed by guessing the element with the second highest likelihood, etc.) Indeed, one might view Guessing Distance as an extension of Guessing Entropy (see Appendix A); however, we prefer Guessing Distance as a measure of security as it provides more information about non-uniform distributions over a key space. For such distributions, Guessing Entropy is increased by the elements that have a low probability, and thus might not provide as conservative an estimate of security as desired. Guessing Distance, on the other hand, can be computed for each user, which brings to light the insecurity afforded by a non-uniform distribution. We provide a concrete example of such a case in Appendix A.

We now show why templates play a crucial role in the computation of

key entropy (

![]() from Section 3). Our analysis

brings to light two points: first that templates, and in particular,

error-correction information, can indeed leak a substantial amount of

information about a key, and thus must be considered when computing

key entropy. Second, we show how standard approaches to computing key

entropy, even if they were to take templates into account, must be

conducted with care to avoid common pitfalls. Through our analysis we

demonstrate the flexibility and utility of Guessing Distance. While

we focus here on a specific proposal by Vielhauer and

Steinmetz [40,41], we argue that our results are generally

applicable to a host of similar proposals (see,

e.g., [44,7,35,17]) that use per-user feature-space

quantization for error correction. This complicates the calculation

of entropy and brings to light common pitfalls.

from Section 3). Our analysis

brings to light two points: first that templates, and in particular,

error-correction information, can indeed leak a substantial amount of

information about a key, and thus must be considered when computing

key entropy. Second, we show how standard approaches to computing key

entropy, even if they were to take templates into account, must be

conducted with care to avoid common pitfalls. Through our analysis we

demonstrate the flexibility and utility of Guessing Distance. While

we focus here on a specific proposal by Vielhauer and

Steinmetz [40,41], we argue that our results are generally

applicable to a host of similar proposals (see,

e.g., [44,7,35,17]) that use per-user feature-space

quantization for error correction. This complicates the calculation

of entropy and brings to light common pitfalls.

|

The construction works as follows. Given 50 features

![]() [40] that map biometric samples to the set of non-negative integers, and

[40] that map biometric samples to the set of non-negative integers, and ![]() enrollment samples

enrollment samples

![]() , let

, let ![]() be the

difference between the minimum and maximum value of

be the

difference between the minimum and maximum value of

![]() , expanded by a small tolerance. The scheme partitions the output range of

, expanded by a small tolerance. The scheme partitions the output range of ![]() into

into ![]() -length

segments. The key is derived by letting

-length

segments. The key is derived by letting ![]() be the smallest

integer in the segment that contains the user's samples, computing

be the smallest

integer in the segment that contains the user's samples, computing

![]() , and setting the

, and setting the

![]() key element

key element

![]() . The key is

. The key is

![]() , and the template

, and the template

![]() is

composed of

is

composed of

![]() . To later extract

. To later extract

![]() given a biometric sample

given a biometric sample

![]() , and a template

, and a template

![]() , set

, set

![]() and

output

and

output

![]() . We refer the

reader to [41] for details on correctness.

. We refer the

reader to [41] for details on correctness.

As is the case in many other proposals, Vielhauer et al. perform an analysis that addresses requirement

![]() by arguing that given that the template leaks only error

correcting information (i.e., the partitioning of the feature space)

it does not indicate the values

by arguing that given that the template leaks only error

correcting information (i.e., the partitioning of the feature space)

it does not indicate the values ![]() . To support this argument, they

conduct an empirical evaluation to measure the Shannon entropy of

each

. To support this argument, they

conduct an empirical evaluation to measure the Shannon entropy of

each ![]() . For each user

. For each user ![]() they derive

they derive

![]() from

from

![]() and

and

![]() , then compute the entropy of each element

, then compute the entropy of each element ![]() across all users. This analysis is a standard estimate of

entropy. To see why this is inaccurate, consider two different users

across all users. This analysis is a standard estimate of

entropy. To see why this is inaccurate, consider two different users

![]() and

and ![]() such that

such that ![]() outputs consistent values on feature

outputs consistent values on feature ![]() and

and ![]() does not. Then the partitioning over

does not. Then the partitioning over ![]() 's range differs

for each user. Thus, even if the mean value of

's range differs

for each user. Thus, even if the mean value of ![]() is the same

when measured over both

is the same

when measured over both ![]() 's and

's and ![]() 's samples, this mean will be

mapped to different partitions in the feature space, and thus, a

different key. This implies that computing entropy over the

's samples, this mean will be

mapped to different partitions in the feature space, and thus, a

different key. This implies that computing entropy over the ![]() overestimates

security because the mapping induced by the templates artificially

amplifies the entropy of the biometrics. A more realistic estimate of

the utility afforded an adversary by auxiliary information can be

achieved by fixing a user's template, and using that template to

error-correct every other user's samples to generate a list of keys,

then measuring how close those keys are to the target user's key.

By conditioning the estimate on the target users template we are able to eliminate the artificial inflation of entropy and provide a

better estimate of the security afforded by the construction.

overestimates

security because the mapping induced by the templates artificially

amplifies the entropy of the biometrics. A more realistic estimate of

the utility afforded an adversary by auxiliary information can be

achieved by fixing a user's template, and using that template to

error-correct every other user's samples to generate a list of keys,

then measuring how close those keys are to the target user's key.

By conditioning the estimate on the target users template we are able to eliminate the artificial inflation of entropy and provide a

better estimate of the security afforded by the construction.

We implemented the construction and tested the technique using all of the passphrases in the data set we collected in [3], which consists of over 9,000 writing samples from 47 users. Each user wrote the same five passphrases 10-20 times. In our analysis we follow the standard approach to isolate the entropy associated with the biometric: we compute various entropy measures using each user's rendering of the same passphrase [29,5,36] (this approach is justified as user selected passphrases are assumed to have low entropy). Tolerance values were set such that the

approach achieved a False Reject Rate (FRR) of ![]() (as reported in [40]) and

all outliers and samples from users who failed to enroll [24]

were removed.

(as reported in [40]) and

all outliers and samples from users who failed to enroll [24]

were removed.

Figure 1 shows three different

measures of key uncertainty. The first measure, denoted Standard, is the common measure of interpersonal variation as

reported in the literature (e.g., [17,7]) using the

data from our experiments. Namely, if the key element ![]() has entropy

has entropy ![]() across the entire population,

then the entropy of the key space is computed as

across the entire population,

then the entropy of the key space is computed as

![]() . We also show two estimates of guessing distance, the first

(

. We also show two estimates of guessing distance, the first

(

![]() , plotted as GD-P) does not take a target user's template into account

and

, plotted as GD-P) does not take a target user's template into account

and ![]() is just the distribution over all other users's keys in the

population (the techniques we use to compute these estimates are described in Appendix B). The second (

is just the distribution over all other users's keys in the

population (the techniques we use to compute these estimates are described in Appendix B). The second (

![]() , plotted as GD-U) takes the

user's template into account, computing

, plotted as GD-U) takes the

user's template into account, computing

![]() by taking

the biometrics from all other users in the population, and generating

keys using

by taking

the biometrics from all other users in the population, and generating

keys using

![]() , then computing the distribution over these

keys.

, then computing the distribution over these

keys.

Figure 1 shows the CDF of the number of guesses

that one would expect an adversary to make to find each user's key.

There are several important points to take away from these results.

The first is the common pitfalls associated with computing key

entropy. The difference between

![]() and the standard

measurement indicates that the standard measurement of entropy (

and the standard

measurement indicates that the standard measurement of entropy (![]() bits in this case) is clearly misleading--under this view one would

expect an adversary to make

bits in this case) is clearly misleading--under this view one would

expect an adversary to make ![]() guesses on average before finding

a key. However, from

guesses on average before finding

a key. However, from

![]() it is clear that an adversary

can do substantially better than this. The difference in estimates is

due to the fact that

it is clear that an adversary

can do substantially better than this. The difference in estimates is

due to the fact that

![]() takes into account conditional

information between features whereas a more standard measure does not.

takes into account conditional

information between features whereas a more standard measure does not.

The second point is the impact of a user's template on computing

![]() . We can see by examining

. We can see by examining

![]() that if we take the

usual approach of just computing entropy over the keys, and ignore

each user's template, we would assume only a small probability of guessing a key in fewer than

that if we take the

usual approach of just computing entropy over the keys, and ignore

each user's template, we would assume only a small probability of guessing a key in fewer than ![]() attempts. On the other hand, since

the templates reduce the possible key space for each user, the

estimate

attempts. On the other hand, since

the templates reduce the possible key space for each user, the

estimate

![]() provides a more realistic

measurement. In fact, an adversary with access to population

statistics has a

provides a more realistic

measurement. In fact, an adversary with access to population

statistics has a ![]() chance of guessing a user's key in fewer than

chance of guessing a user's key in fewer than

![]() attempts, and

attempts, and ![]() chance guessing a key in a single attempt!

chance guessing a key in a single attempt!

These results also shed light on another pitfall worth

mentioning--namely, that of reporting an average case estimate of key

strength. If we take the target user's template into account in the

current construction, ![]() of the keys can be guessed in

one attempt despite the estimated Guessing Entropy being approximately

of the keys can be guessed in

one attempt despite the estimated Guessing Entropy being approximately

![]() . In summary, this analysis highlights the importance of conditioning entropy estimates on publicly available templates, and how several common entropy measures can result in misleading estimates of security.

. In summary, this analysis highlights the importance of conditioning entropy estimates on publicly available templates, and how several common entropy measures can result in misleading estimates of security.

Recall that a scheme that achieves Weak Biometric Privacy uses

templates that do not leak information about the biometrics input

during enrollment. A standard approach to arguing that a scheme

achieves

![]() is to show (1) auxiliary information leaks little

useful information about the biometrics, and (2) templates do not leak

information about a biometric. This can be problematic as the two

steps are generally performed in isolation. In our description of

is to show (1) auxiliary information leaks little

useful information about the biometrics, and (2) templates do not leak

information about a biometric. This can be problematic as the two

steps are generally performed in isolation. In our description of

![]() , however, we argue that step (2) should actually show that

an adversary with access to both templates and auxiliary

information should learn no information about the biometric. The key

difference here is that auxiliary information is used in both steps

(1) and (2). This is essential as it is not difficult to create

templates that are secure when considered in isolation, but are

insecure once we consider knowledge derived from other users

(e.g., population-wide statistics). In what follows we shed light on

this important consideration by examining the scheme of Hao and

Wah [17]. While our analysis focuses on their construction, it

is pertinent to any BKG that stores partial information about the

biometric in the template [43,26].

, however, we argue that step (2) should actually show that

an adversary with access to both templates and auxiliary

information should learn no information about the biometric. The key

difference here is that auxiliary information is used in both steps

(1) and (2). This is essential as it is not difficult to create

templates that are secure when considered in isolation, but are

insecure once we consider knowledge derived from other users

(e.g., population-wide statistics). In what follows we shed light on

this important consideration by examining the scheme of Hao and

Wah [17]. While our analysis focuses on their construction, it

is pertinent to any BKG that stores partial information about the

biometric in the template [43,26].

For completeness, we briefly review the construction. The BKG

generates DSA signing keys from ![]() dynamic features associated with

handwriting (e.g., pen tip velocity or writing time). The range of

each feature is quantized based on a user's natural variation over the

feature. Each partition of a feature's range is assigned a unique

integer; let

dynamic features associated with

handwriting (e.g., pen tip velocity or writing time). The range of

each feature is quantized based on a user's natural variation over the

feature. Each partition of a feature's range is assigned a unique

integer; let ![]() be the integer that corresponds to the partition

containing the output of feature

be the integer that corresponds to the partition

containing the output of feature ![]() when applied to the user's

biometric. The signing key is computed as

when applied to the user's

biometric. The signing key is computed as

![]() . The template stores information that

describes the partitions for each feature, as well as the

. The template stores information that

describes the partitions for each feature, as well as the ![]() coordinates that define the pen strokes of the enrollment samples, and

the verification key corresponding to

coordinates that define the pen strokes of the enrollment samples, and

the verification key corresponding to

![]() . The

. The ![]() coordinates

of the enrollment samples are used as input to the Dynamic Time

Warping [32] algorithm during subsequent key generation; if the

provided sample diverges too greatly from the original samples, it is

immediately rejected and key generation aborted.

coordinates

of the enrollment samples are used as input to the Dynamic Time

Warping [32] algorithm during subsequent key generation; if the

provided sample diverges too greatly from the original samples, it is

immediately rejected and key generation aborted.

|

Hao et al. performed a typical analysis of

![]() [17].

First, they compute the entropy of the features over the entire

population of users to show that auxiliary information leaks little

information that could be used to discern the biometric. Second, the

template is argued to be secure by making the following three

observations. First, since the template only specifies the

partitioning of the range of each feature, the template only leaks the

variation in each feature, not the output. Second, for a

computationally bound adversary, a DSA verification key leaks no

information about the DSA signing key. Third, since the BKG employs

only dynamic features, the static

[17].

First, they compute the entropy of the features over the entire

population of users to show that auxiliary information leaks little

information that could be used to discern the biometric. Second, the

template is argued to be secure by making the following three

observations. First, since the template only specifies the

partitioning of the range of each feature, the template only leaks the

variation in each feature, not the output. Second, for a

computationally bound adversary, a DSA verification key leaks no

information about the DSA signing key. Third, since the BKG employs

only dynamic features, the static ![]() coordinates leak no relevant

information. Note that in this analysis the template is analyzed without considering auxiliary information. Unfortunately, while by

themselves the auxiliary information and the templates seem to be of

little use to an adversary, when taken together, the biometric can be

easily recovered.

coordinates leak no relevant

information. Note that in this analysis the template is analyzed without considering auxiliary information. Unfortunately, while by

themselves the auxiliary information and the templates seem to be of

little use to an adversary, when taken together, the biometric can be

easily recovered.

To empirically evaluate our attack, we used the same data set as in

Section 5. Our implementation of the BKG had a FRR of

29.2% and a False Accept Rate (FAR) of ![]() , which is inline with

the FRR/FAR of 28%/1.2% reported in [17].

Moreover, if we follow the computation of inter-personal variation as

described in [17], then we would incorrectly conclude that the

scheme creates keys with over 40 bits of entropy with our data set,

which is the same estimate provided in [17]. However, this is

not the case (see Figure 2). In particular, the

fact that the template leaks information about the biometric enables

an attack that successfully recreates the key

, which is inline with

the FRR/FAR of 28%/1.2% reported in [17].

Moreover, if we follow the computation of inter-personal variation as

described in [17], then we would incorrectly conclude that the

scheme creates keys with over 40 bits of entropy with our data set,

which is the same estimate provided in [17]. However, this is

not the case (see Figure 2). In particular, the

fact that the template leaks information about the biometric enables

an attack that successfully recreates the key ![]() of the time

on the first try; approximately

of the time

on the first try; approximately ![]() of the keys are

correctly identified after making fewer than

of the keys are

correctly identified after making fewer than ![]() guesses. In

summary, the significance of this analysis does not lie in the

effectiveness of the described attack, but more so in the fact that

the original analysis failed to take auxiliary information into

consideration when evaluating the security of the template.

guesses. In

summary, the significance of this analysis does not lie in the

effectiveness of the described attack, but more so in the fact that

the original analysis failed to take auxiliary information into

consideration when evaluating the security of the template.

Lastly, we highlight the importance of quantifying the privacy of a

user's biometric against adversaries who have access to the

cryptographic key (i.e.,

![]() from Section 3).

We examine a BKG proposed by Hao et al. [16].4 The construction generates a

random key and then "locks" it with a user's iris code. The

construction uses a cryptographic hash function

from Section 3).

We examine a BKG proposed by Hao et al. [16].4 The construction generates a

random key and then "locks" it with a user's iris code. The

construction uses a cryptographic hash function

![]() and a "concatenated" error correction code consisting of an

encoding algorithm

and a "concatenated" error correction code consisting of an

encoding algorithm

![]() , and the

corresponding decoding algorithm

, and the

corresponding decoding algorithm

![]() . This error correction code is the composition of a

Reed-Solomon and Hadamard code [16, Section 3]. Iris codes

are elements in

. This error correction code is the composition of a

Reed-Solomon and Hadamard code [16, Section 3]. Iris codes

are elements in

![]() [8].

[8].

The BKG works as follows: given a user's iris code

![]() ,

select a random string

,

select a random string

![]() , and derive the template

, and derive the template

![]() , and

output

, and

output

![]() and

and

![]() . To later derive the key given an iris

code

. To later derive the key given an iris

code

![]() and the template

and the template

![]() , compute

, compute

![]() . If

. If

![]() , then output

, then output

![]() , otherwise, fail. If

, otherwise, fail. If

![]() and

and

![]() are "close" to one another, then

are "close" to one another, then

![]() is "close" to

is "close" to

![]() , perhaps differing in only a

few bits. The error correcting code handles these errors, yielding

, perhaps differing in only a

few bits. The error correcting code handles these errors, yielding

![]() .

.

Hao et al. provide a security analysis arguing requirement

![]() using both cryptographic reasoning and a standard estimate of entropy

of the input biometric. That is, they provide empirical evidence that

auxiliary information cannot be used to guess a target user's

biometric, and a cryptographic argument that, assuming the former, the

template and auxiliary information cannot be used to guess a key.

They conservatively estimate the entropy of

using both cryptographic reasoning and a standard estimate of entropy

of the input biometric. That is, they provide empirical evidence that

auxiliary information cannot be used to guess a target user's

biometric, and a cryptographic argument that, assuming the former, the

template and auxiliary information cannot be used to guess a key.

They conservatively estimate the entropy of

![]() to be 44

bits. Moreover, the authors note that if the key is ever compromised,

the system can be used to "lock" a new key, since

to be 44

bits. Moreover, the authors note that if the key is ever compromised,

the system can be used to "lock" a new key, since

![]() is selected

at random and is not a function of the biometric.

is selected

at random and is not a function of the biometric.

Unfortunately, given the current construction, compromise of

![]() ,

in addition to the public information

,

in addition to the public information

![]() , allows one to completely reconstruct

, allows one to completely reconstruct

![]() . Thus, even if a user were to create a new template and

key pair, an adversary could use the old template and key to derive

the biometric, and then use the biometric to unlock the new key. The

significance of this is worth restating: because this BKG fails to

meet

. Thus, even if a user were to create a new template and

key pair, an adversary could use the old template and key to derive

the biometric, and then use the biometric to unlock the new key. The

significance of this is worth restating: because this BKG fails to

meet

![]() , the privacy of a user's biometric is completely

undermined once any key for that user is ever compromised.

, the privacy of a user's biometric is completely

undermined once any key for that user is ever compromised.

To underscore the practical significance of each of these

requirements, we present analyses of three published systems. While

we point out weaknesses in specific constructions, it is not our goal

to fault the those specific works. Instead, we aim to bring to light

flaws in the standard approaches that were followed in each setting.

In one case we exploit auxiliary information to show that an attacker

can guess ![]() of the keys on her first attempt. In another case,

we highlight the importance of ensuring biometric privacy by

exploiting the information leaked by templates to yield a

of the keys on her first attempt. In another case,

we highlight the importance of ensuring biometric privacy by

exploiting the information leaked by templates to yield a ![]() chance of guessing a user's key in one attempt. Lastly, we show that

subtleties in BKG design can lead to flaws that allow an adversary to

derive a user's biometric given a compromised key and template,

thereby completely undermining the security of the scheme.

chance of guessing a user's key in one attempt. Lastly, we show that

subtleties in BKG design can lead to flaws that allow an adversary to

derive a user's biometric given a compromised key and template,

thereby completely undermining the security of the scheme.

We hope that our work encourages designers and evaluators to analyze BKGs with a degree of skepticism, and to question claims of security that overlook the requirements presented herein. To facilitate this type of approach, we not only ensure that our requirements can be applied to real systems, but also introduce Guessing Distance--a heuristic measure that estimates the uncertainty of the outputs of a BKG given access to population statistics.

Guessing Entropy [25] is commonly used for measuring the

expected number of guesses it takes to find an average element in a

set assuming an optimal guessing strategy (i.e., first guessing the

element with the highest likelihood, followed by guessing the element

with the second highest likelihood, etc.). Given a distribution ![]() over

over ![]() and the convention that

and the convention that

![]() , Guessing Entropy is computed as

, Guessing Entropy is computed as

![]() .

.

Guessing Entropy is commonly used to determine how many guesses an adversary will take to guess a key. At first, Guessing Entropy and Guessing Distance appear to be quite similar. However, there is one important difference: Guessing Entropy is a summary statistic and Guessing Distance is not. While Guessing Entropy provides an intuitive and accurate estimate over distributions that are close to uniform, the fact that there is one measure of strength for all users in the population may result in somewhat misleading results when Guessing Entropy is computed over skewed distributions.

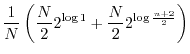

To see why this is the case, consider the following distribution: let

![]() be defined over

be defined over

![]() as

as

![]() , and

, and

![]() for

for

![]() . That is, one element (or key) is output by 50% of

the users and the remaining elements are output with equal likelihood.

The Guessing Entropy of

. That is, one element (or key) is output by 50% of

the users and the remaining elements are output with equal likelihood.

The Guessing Entropy of ![]() is:

is:

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

Thus, although the expected number of guesses to correctly select ![]() is approximately

is approximately

![]() , over half of the population's keys are correctly guessed on the first attempt following the optimal strategy. To contrast this, consider an analysis of Guessing Distance with threshold

, over half of the population's keys are correctly guessed on the first attempt following the optimal strategy. To contrast this, consider an analysis of Guessing Distance with threshold

![]() . (Assume for exposition that distributions are estimated from a population of

. (Assume for exposition that distributions are estimated from a population of

![]() users.) To do so, evaluate each user in the population independently. Given a population of users, first remove a user to compute

users.) To do so, evaluate each user in the population independently. Given a population of users, first remove a user to compute

![]() and use the remaining users to compute

and use the remaining users to compute ![]() . Repeat this process for the entire population.

. Repeat this process for the entire population.

In the case of our pathological distribution, we may consider only two users without loss of generality: a user with distribution

![]() who outputs key

who outputs key ![]() , and user with distribution

, and user with distribution

![]() who outputs key

who outputs key ![]() . In the first case, we have

. In the first case, we have

![]() , because the majority of the mass according to

, because the majority of the mass according to ![]() is assigned to

is assigned to ![]() , which is the most likely element according to

, which is the most likely element according to

![]() . For

. For

![]() , we have

, we have ![]() and

and ![]() , and thus

, and thus

![]() . Taking the minimum value (or even reporting a CDF) shows that for a large proportion of the population (all users with distribution

. Taking the minimum value (or even reporting a CDF) shows that for a large proportion of the population (all users with distribution

![]() ), this distribution offers no security--a fact that is immediately lost if we only consider a summary statistic. However, it is comforting to note, that if we compute the average of

), this distribution offers no security--a fact that is immediately lost if we only consider a summary statistic. However, it is comforting to note, that if we compute the average of

![]() over all users, we obtain estimates that are identical to that of guessing entropy for sets that are sufficiently large:

over all users, we obtain estimates that are identical to that of guessing entropy for sets that are sufficiently large:

|

|

||

|

|||

As noted in Section 5, it is difficult to obtain a

meaningful estimate of probability distributions over large sets,

e.g.,

![]() . In order to quantify the security defined by a

system, it is necessary to find techniques to derive meaningful

estimates. This Appendix discusses how we estimate

. In order to quantify the security defined by a

system, it is necessary to find techniques to derive meaningful

estimates. This Appendix discusses how we estimate

![]() . The

estimate also implicitely defines an algorithm that can be used to

guess keys.

. The

estimate also implicitely defines an algorithm that can be used to

guess keys.

For convenience we use ![]() to denote both a biometric feature and

the random variable that is defined using population statistics over

to denote both a biometric feature and

the random variable that is defined using population statistics over

![]() (taken over the set

(taken over the set

![]() ). If a distribution is not

subscripted, it is understood to be taken over the key space

). If a distribution is not

subscripted, it is understood to be taken over the key space

![]() . Our estimate

uses of several tools from information theory:

. Our estimate

uses of several tools from information theory:

![$\displaystyle H(X) = -\sum_{\omega \in \Omega} {\Pr\left[{X = \omega}\right]} \log {\Pr\left[{X =

\omega}\right]}

$](img151.png)

![$\displaystyle I(X,Y) = \sum_{x \in \Omega_x}\sum_{y \in \Omega_y} {\Pr\left[{X ...

...[{X = x \wedge Y = y}\right]}}{{\Pr\left[{X=x}\right]}{\Pr\left[{Y=y}\right]}}

$](img155.png)

We use the notation

Let

![]() be the guessing distance between the user's and population's

distribution over

be the guessing distance between the user's and population's

distribution over ![]() conditioned on the even that

conditioned on the even that

![]() . In particular,

let

. In particular,

let

![]() be the elements

of

be the elements

of

![]() ordered such that

ordered such that

As before, let

Then,

The weights of elements that are more likely to occur given the values of other features will be larger than the weights that are less likely to occur. Intuitively, each of the values (![]() ) has an

influence on

) has an

influence on

![]() and those values that correspond to features that have a higher correlation with

and those values that correspond to features that have a higher correlation with ![]() have more influence. We also note that we only use two levels of conditional probabilities, which are relatively easy to compute, instead of conditioning over the entire space. Now, we use the weights to estimate the probability distributions as:

have more influence. We also note that we only use two levels of conditional probabilities, which are relatively easy to compute, instead of conditioning over the entire space. Now, we use the weights to estimate the probability distributions as:

|

Note that while this technique may not provide a perfect estimate of each probability, our goal is to discover the relative magnitude of the probabilities because they will be used to estimate Guessing Distance. We believe that this approach achieves this goal.

We are almost ready to provide an estimate of

![]() . First, we specify an ordering for the features. The ordering will be according to an ordering measure (

. First, we specify an ordering for the features. The ordering will be according to an ordering measure (![]() ) such that features with a larger measure have a low entropy (and are therefore easier to guess) and have a high correlation with other features. An adversary could then use this ordering to reduce the number of guesses in a search by first guessing features with a higher measure. Define the feature-ordering measure for

) such that features with a larger measure have a low entropy (and are therefore easier to guess) and have a high correlation with other features. An adversary could then use this ordering to reduce the number of guesses in a search by first guessing features with a higher measure. Define the feature-ordering measure for ![]() as:

as:

|

Finally, we reindex the features such that

![]() for all

for all

![]() , and estimate the guessing distance for a specific user with

, and estimate the guessing distance for a specific user with

![]() as:

as:

|

This estimate helps in modeling an adversary that performs a

brute-force search over all of the features by starting with the

features that are easiest to guess and using those features to reduce the uncertainty about features that are more difficult to guess. For each feature, the adversary

will need to make

![]() guesses

to find the correct value. Since each incorrect guess

(

guesses

to find the correct value. Since each incorrect guess

(

![]() of them) will cause

a fruitless enumeration of the rest of the features, we

multiply the number of incorrect guesses by the sizes of the ranges of

the remaining features. Finally, we take the log to represent the

number of guesses as bits.

of them) will cause

a fruitless enumeration of the rest of the features, we

multiply the number of incorrect guesses by the sizes of the ranges of

the remaining features. Finally, we take the log to represent the

number of guesses as bits.

Section 5 uses this estimation technique to measure

![]() of a user versus the population (

of a user versus the population (

![]() ), and for a user versus the population conditioned on the user's template (

), and for a user versus the population conditioned on the user's template (

![]() ). The only way in which the estimation technique differs between the two settings is the definition of

). The only way in which the estimation technique differs between the two settings is the definition of

![]() . In the case of

. In the case of

![]() ,

,

![]() is computed by measuring the

is computed by measuring the

![]() key element for every other user in the population. In the case of

key element for every other user in the population. In the case of

![]() ,

,

![]() is computed using all of the other user's samples in conjuction with the target user's template to derive a set of keys and taking the distribution over the

is computed using all of the other user's samples in conjuction with the target user's template to derive a set of keys and taking the distribution over the ![]() th element of the keys.

th element of the keys.