5th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies - Paper Pp. 31–45 of the Proceedings

A Five-Year Study of

File-System Metadata

Nitin Agrawal

University of Wisconsin, Madison

nitina@cs.wisc.edu

|

William

J. Bolosky, John R. Douceur, Jacob R. Lorch

Microsoft Research

{bolosky,johndo,lorch}@microsoft.com

|

Abstract:

For five years, we collected annual snapshots of file-system metadata from over 60,000 Windows PC file systems in a large corporation. In this paper, we use these snapshots to study temporal changes in file size, file age, file-type frequency, directory size, namespace structure, file-system population, storage capacity and consumption, and degree of file modification. We present a generative model that explains the namespace structure and the distribution of directory sizes. We find significant temporal trends relating to the popularity of certain file types, the origin of file content, the way the namespace is used, and the degree of variation among file systems, as well as more pedestrian changes in sizes and capacities. We give examples of consequent lessons for designers of file systems and related software.

1 Introduction

Every year from 2000 to 2004, we collected snapshots of metadata from over ten thousand file systems on the Windows desktop computers at Microsoft Corporation. We gathered this data by mass-emailing a scanning program to Microsoft's employees, and we had a 22% participation rate every year. Our resulting datasets contain metadata from 63,398 distinct file systems, 6457 of which provided snapshots in multiple years. This project was a longitudinal extension of an earlier study we performed in 1998 [9], which was an order of magnitude larger than any prior study of file-system metadata. Our earlier study involved a single capture of file-system metadata, and it focused on lateral variation among file systems at a moment in time. By contrast, the present study focuses on longitudinal changes in file systems over a five-year time span. In particular, we study temporal changes in the size, age, and type frequency of files; the size of directories; the structure of the file-system namespace; and various characteristics of file systems, including file and directory population, storage capacity, storage consumption, and degree of file modification. The contributions of this work are threefold. First, we contribute the collected data set, which we will sanitize and make available for general use later this year. This is the largest set of file-system metadata ever collected, and it spans the longest time period of any sizeable metadata collection. To obtain this data set, contact the Microsoft authors. Second, we contribute all of our research observations, including:

- The space used in file systems has increased over the course of

our study, not only because mean file size has increased (from

108 KB to 189 KB), but also because the number of files has

increased (from 30K to 90K).

- Eight file-name extensions account for over 35% of files, and

nine file-name extensions account for over 35% of the bytes in files.

The same sets of extensions have remained popular for many years.

- The fraction of file-system content created or modified locally

has decreased over time. In the first year of our study, the median

file system had 30% of its files created or modified locally, and four

years later this percentage was 22%.

- Directory size distribution has not notably changed over the

years of our study. In each year, directories have had very few

subdirectories and a modest number of entries. 90% of them have had two

or fewer subdirectories, and 90% of them have had 20 or fewer total

entries.

- The fraction of file system storage residing in the namespace

subtree meant for user documents and settings has increased in every

year of our study, starting at 7% and rising to 15%. The fraction

residing in the subtree meant for system files has also risen over the

course of our study, from 2% to 11%.

- File system capacity has increased dramatically during our study,

with median capacity rising from 5 GB to 40 GB. One might

expect this to cause drastic reductions in file system fullness, but

instead the reduction in file system fullness has been modest. Median

fullness has only decreased from 47% to 42%.

- Over the course of a single year, 80% of file systems become

fuller and 18% become less full.

Third, we contribute a generative, probabilistic model for how

directory

trees are created. Our model explains the distribution of directories

by

depth in the namespace tree, and it also explains the distribution of

the

count of subdirectories per directory. This is the first generative

model

that characterizes the process by which file-system namespaces are

constructed.

§2 describes the methodology of

our data collection,

analysis, and presentation. §3, §4,

and §5 present our findings on,

respectively, files,

directories, and space usage. §6

surveys related work,

and §7 summarizes and concludes.

2 Methodology

This section describes the methodology we applied to collecting,

analyzing,

and presenting the data.

We developed a simple program that traverses the directory tree of each

local,

fixed-disk file system mounted on a computer. The program records a

snapshot

of all metadata associated with each file or directory, including

hidden files

and directories. This metadata includes name, size, timestamps, and

attributes. The program also records the parent-child relationships of

nodes

in the namespace tree, as well as some system configuration

information. The

program records file names in an encrypted form. We wrote automated

tools

that decrypt the file names for computing aggregate statistics, but for

privacy reasons we do not look at the decrypted file names directly,

which

places some limits on our analyses. In post-processing, we remove

metadata

relating to the system paging file, because this is part of the virtual

memory

system rather than the file system.

In the autumn of every year from 2000 to 2004, we distributed the

scanning

program via email to a large subset of the employees of Microsoft, with

a

request for the recipients to run the program on their desktop

machines. As

an incentive to participate, we held a lottery in which each scanned

machine

counted as an entry, with a single prize of a night's stay at a nearby

resort

hotel. The specific subset of people we were permitted to poll varied

from

year to year based on a number of factors; however, despite variations

in user

population and in other distribution particulars, we observed a 22%

participation rate every year.

We scanned desktops rather than servers because at Microsoft, files

are

typically stored on individual desktops rather than centralized

servers. We

collected the data via voluntary participation rather than random

selection

because the company only permitted the former approach; note that this

voluntary approach may have produced selection bias.

Table 1 itemizes some

properties of each year's data

collection. The primary collection period ran between the listed start

and

end dates, which mark the beginning of our emailing requests and the

last

eligible day for the lottery. Some snapshots continued to trickle in

after

the primary collection period; we used these in our analyses as well.

Table 2 itemizes the breakdown

of each year's snapshots

according to file-system type. 80% of our snapshots came from

NTFS [27], the main file

system for operating systems in the

Windows NT family; 5% from FAT [18], a 16-bit file system dating

from DOS; and 15% from FAT32 [18],

a 32-bit upgrade of FAT

developed for Windows 95.

Table 1:

Properties of each year's dataset

| Year |

Period |

Users |

Machs |

FSs |

| 2000 |

13 Sep - 29 Sep |

5396 |

6051 |

11,654 |

| 2001 |

8 Oct - 2 Nov |

7539 |

9363 |

16,022 |

| 2002 |

30 Sep - 1 Nov |

7158 |

9091 |

15,011 |

| 2003 |

13 Oct - 14 Nov |

7436 |

9262 |

14,633 |

| 2004 |

5 Oct - 12 Nov |

7180 |

8729 |

13,505 |

|

Table 2:

File system types in datasets

| Year |

NTFS |

FAT32 |

FAT |

Other |

Total |

| 2000 |

7,015 |

2,696 |

1,943 |

0 |

11,654 |

| 2001 |

11,791 |

3,314 |

915 |

2 |

16,022 |

| 2002 |

12,302 |

2,280 |

429 |

0 |

15,011 |

| 2003 |

12,853 |

1,478 |

302 |

0 |

14,633 |

| 2004 |

12,364 |

876 |

264 |

1 |

13,505 |

| Total |

56,325 |

10,644 |

3,853 |

3 |

70,825 |

|

For some analyses, we needed a way to establish whether two file-system

snapshots from different years refer to the same file system.

``Sameness'' is

not actually a well-formed notion; for example, it is not clear whether

a file

system is still the same after its volume is extended. We defined two

snapshots to refer to the same file system if and only if they have the

same

user name, computer name, volume ID, drive letter, and total space. The

need

for some of these conditions was not obvious at first. For example, we

added

drive letter because some drives on some machines are multiply mapped,

and we

added total space so that a volume set would not be considered the same

if a

new volume were added to the set. Based on this definition,

Table 3 shows the number

of snapshots for which

we have consecutive-year information.

Table 3:

Number of file systems for which we have snapshots in the  consecutive years starting with each year. For instance,

there are 1,852 file systems for which we have snapshots from both 2002

and 2003. consecutive years starting with each year. For instance,

there are 1,852 file systems for which we have snapshots from both 2002

and 2003.

| Start |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 2000 |

11,654 |

950 |

234 |

63 |

18 |

| 2001 |

16,022 |

1,833 |

498 |

144 |

- |

| 2002 |

15,011 |

1,852 |

588 |

- |

- |

| 2003 |

14,633 |

1,901 |

- |

- |

- |

| 2004 |

13,505 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Total |

70,825 |

6,536 |

1,320 |

207 |

18 |

|

Many of our graphs have horizontal axes that span a large range of

nonnegative

numbers. To represent these ranges compactly, we use a logarithmic

scale for

non-zero values, but we also include an abscissa for the zero value,

even

though zero does not strictly belong on a logarithmic scale.

We plot most histograms with line graphs rather than bar graphs

because, with

five or more datasets on a single plot, bar graphs can become difficult

to

read. For each bin in the histogram, we plot a point  where where  is

the midpoint of the bin and is

the midpoint of the bin and  is the size of the

bin. We use the geometric

midpoint when the is the size of the

bin. We use the geometric

midpoint when the  axis uses a logarithmic scale. We

often plot

un-normalized histograms rather than probability density functions

(PDFs) for

two reasons: First, the graphs expose more data if we do not normalize

them.

Second, because the count of files and directories per file system has

grown

substantially over time, not normalizing allows us to plot multiple

years'

curves on the same chart without overlapping to the point of

unreadability. axis uses a logarithmic scale. We

often plot

un-normalized histograms rather than probability density functions

(PDFs) for

two reasons: First, the graphs expose more data if we do not normalize

them.

Second, because the count of files and directories per file system has

grown

substantially over time, not normalizing allows us to plot multiple

years'

curves on the same chart without overlapping to the point of

unreadability.

Whenever we use the prefix K, as in KB, we mean  .

Similarly, we use M

for .

Similarly, we use M

for  and G for and G for  . .

We believe that analysis of longitudinal file system data is of

interest to

many sets of people with diverse concerns about file system usage. For

instance:

- developers of file systems, including desktop, server, and

distributed file systems

- storage area network designers

- developers of file system utilities, such as backup, anti-virus,

content indexing, encryption, and disk space usage visualization

- storage capacity planners

- disk manufacturers, especially those using gray-box techniques to

enable visibility into the file system at the disk level [2]

- multitier storage system developers

In each subsection, after discussing our findings and what we consider

to be

the most interesting summaries of these findings, we will present some

examples of interesting implications for the people enumerated above.

All our data comes from a relatively homogenous sample of machines:

Microsoft

desktops running Windows. Since past studies [23,28]

have

shown that file system characteristics can vary from one environment to

another, our conclusions may not be applicable to substantially

different

environments. For instance, our conclusions are likely not applicable

to file

system server workloads, and it is unclear to what extent they can be

generalized to non-Windows operating systems. It may also be that

artifacts

of Microsoft policy, such as specific software distributions that are

common

or disallowed, may yield results that would not apply to other

workloads.

3 Files

3.1 File count per file system

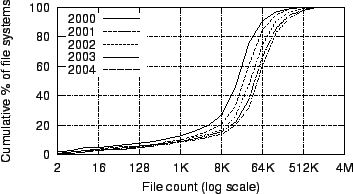

Figure 1:

CDFs of file systems by file count

|

Figure 1

plots cumulative

distribution functions (CDFs) of file systems by count of files. The

count of

files per file system has increased steadily over our five-year sample

period:

The arithmetic mean has grown from 30K to 90K files and the median has

grown

from 18K to 52K files.

The count of files per file system is going up from year to year,

and, as we

will discuss in §4.1,

the same holds

for directories. Thus, file system designers should ensure their

metadata

tables scale to large file counts. Additionally, we can expect file

system

scans that examine data proportional to the number of files and/or

directories

to take progressively longer. Examples of such scans include virus

scans and

metadata integrity checks following block corruption. Thus, it will

become

increasingly useful to perform these checks efficiently, perhaps by

scanning

in an order that minimizes movement of the disk arm.

This section describes our findings regarding file size. We report the

size

of actual content, ignoring the effects of internal fragmentation, file

metadata, and any other overhead. We observe that the overall file size

distribution has changed slightly over the five years of our study. By

contrast, the majority of stored bytes are found in increasingly larger

files.

Moreover, the latter distribution increasingly exhibits a double mode,

due

mainly to database and blob (binary large object) files.

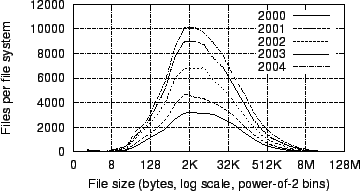

Figure 2:

Histograms of files by size

|

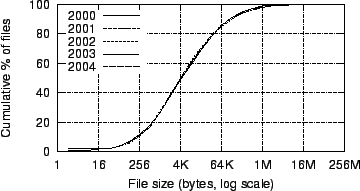

Figure 3:

CDFs of files by size

|

Figure 2 plots

histograms of files by size

and Figure 3 plots the

corresponding CDFs. We

see that the absolute count of files per file system has grown

significantly

over time, but the general shape of the distribution has not changed

significantly. Although it is not visible on the graph, the arithmetic

mean

file size has grown by 75% from 108 KB to 189 KB. In each

year, 1-1.5% of

files have a size of zero.

The growth in mean file size from 108 KB to 189 KB over

four years suggests

that this metric grows roughly 15% per year. Another way to estimate

this

growth rate is to compare our 2000 result to the 1981 result of

13.4 KB

obtained by Satyanarayanan [24].

This comparison estimates the

annual growth rate as 12%. Note that this latter estimate is somewhat

flawed, since it compares file sizes from two rather different

environments.

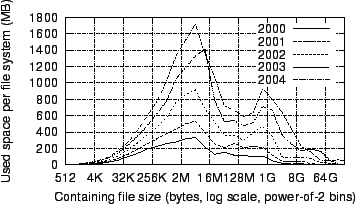

Figure 4:

Histograms of bytes by containing file

size

|

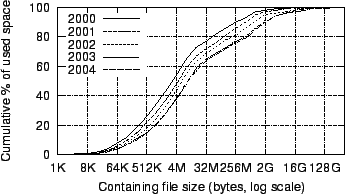

Figure 5:

CDFs of bytes by containing file

size

|

Figure 4

plots histograms

of bytes by containing file size, alternately described as histograms

of files

weighted by file size. Figure 5

plots CDFs of these distributions. We observe that the distribution of

file

size has shifted to the right over time, with the median weighted file

size increasing

from 3 MB to 9 MB. Also, the distribution exhibits a double

mode that has

become progressively more pronounced. The corresponding distribution in

our

1998 study did not show a true second mode, but it did show an

inflection

point around 64 MB, which is near the local minimum in

Figure 4.

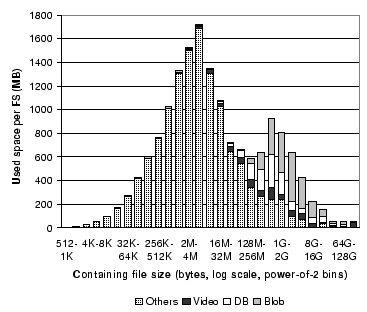

Figure 6:

Contribution of file types to Figure 4 (2004). Video

means files with extension avi, dps, mpeg,

mpg, vob, or wmv; DB means files

with extension ldf, mad, mdf, ndf,

ost, or pst; and Blob means files named hiberfil.sys

and files with extension bak, bkf, bkp, dmp,

gho, iso, pqi, rbf, or vhd.

|

To study this second peak, we broke out several categories of files

according

to file-name extension.

Figure 6

replots the 2004 data from

Figure 4

as a stacked bar

chart, with the contributions of video, database, and blob files

indicated.

We see that most of the bytes in large files are in video, database,

and blob

files, and that most of the video, database, and blob bytes are in

large

files.

Our finding that different types of files have different size

distributions

echoes the findings of other studies. In 1981, Satyanarayanan [24]

found this to be the case on a shared file server in an academic

environment.

In 2001, Evans and Kuenning also noted this phenomenon in their

analysis of 22

machines running various operating systems at Harvey Mudd College and

Marine

Biological Laboratories [11].

The fact that this finding is

consistent across various different environments and times suggests

that it is

fundamental.

There are several implications of the fact that a large number of

small files

account for a small fraction of disk usage, such as the following.

First, it

may not take much space to colocate many of these files with their

metadata.

This may be a reasonable way to reduce the disk seek time needed to

access

these files. Second, a file system that colocates several files in a

single

block, like ReiserFS [22],

will have many opportunities to do so.

This will save substantial space by eliminating internal fragmentation,

especially if a large block size is used to improve performance. Third,

designers of disk usage visualization utilities may want to show not

only

directories but also the names of certain large files.

This subsection describes our findings regarding file age. Because file

timestamps can be modified by application programs [17], our

conclusions should be regarded cautiously.

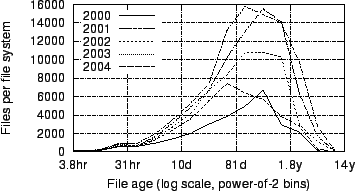

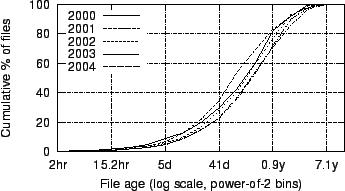

Figure 7:

Histograms of files by age

|

Figure 8:

CDFs of files by age

|

Figure 7 plots

histograms of files by age,

calculated as the elapsed time since the file was created or last

modified,

relative to the time of the snapshot. Figure 8

shows CDFs of this same data. The median file age ranges between 80 and

160

days across datasets, with no clear trend over time.

The distribution of file age is not memoryless, so the age of a file

is useful

in predicting its remaining lifetime. So, systems such as archival

backup

systems can use this distribution to make predictions of how much

longer a

file will be needed based on how old it is. Since the distribution of

file

age has not appreciably changed across the years, we can expect that a

prediction algorithm developed today based on the latest distribution

will

apply for several years to come.

This subsection describes our findings regarding popular file types, as

determined by file-name extension. Although the top few extensions have

not

changed dramatically over our five-year sample period, there has been

some

change, reflecting a decline in the relative prevalence of web content

and an

increase in use of virtual machines. The top few extensions account for

nearly half of all files and bytes in file systems.

In old DOS systems with 8.3-style file names, the extension was the

zero to

three characters following the single dot in the file name. Although

Windows

systems allow file names of nearly arbitrary length and containing

multiple

dots, many applications continue to indicate their file types by means

of

extensions. For our analyses, we define an extension as the

five-or-fewer

characters following the last dot in a file name. If a name has no dots

or

has more than five characters after the last dot, we consider that name

to

have no extension, which we represent with the symbol Ø. As a

special case,

if a file name ends in .gz, .bz2, and .Z,

then we

ignore that suffix when determining extension. We do this because these

are

types of compressed files wherein the actual content type is indicated

by the

characters prior to the compression extension. To understand the

typical

usage of the file extensions we discuss in this section, see

Table 4.

Table 4:

Typical usage of popular file extensions

| Extension |

Typical Usage |

| cpp |

C++ source code |

| dll |

Dynamic link library |

| exe |

Executable |

| gif |

Image in Graphic Interchange Format |

| h |

Source code header |

| htm |

File in hypertext markup language |

| jpg |

Image in JPEG format |

| lib |

Code library |

| mp3 |

Music file in MPEG Layer III format |

| pch |

Precompiled header |

| pdb |

Source symbols for debugging |

| pst |

Outlook personal folder |

| txt |

Text |

| vhd |

Virtual hard drive for virtual machine |

| wma |

Windows Media Audio |

|

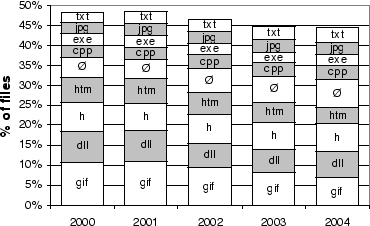

Figure 9:

Fraction of files with popular extensions

|

Figure 10:

Fraction of bytes in files with popular extensions

|

Figure 9

plots, for the nine

extensions that are the most popular in terms of file count, the

fraction of

files with that extension. The fractions are plotted longitudinally

over our

five-year sample period. The most notable thing we observe is that

these

extensions' popularity is relatively stable--the top five extensions

have

remained the top five for this entire time. However, the relative

popularity

of gif files and htm files has gone down steadily

since

2001, suggesting a decline in the popularity of web content relative to

other

ways to fill one's file system.

Figure 10

plots, for

the ten extensions that are the most popular in terms of summed file

size, the

fraction of file bytes residing in files with that extension. Across

all

years, dynamic link libraries (dll files) contain more bytes

than any

other file type. Extension vhd, which is used for virtual

hard

drives, is consuming a rapidly increasing fraction of file-system

space,

suggesting that virtual machine use is increasing. The null extension

exhibits a notable anomaly in 2003, but we cannot investigate the cause

without decrypting the file names in our datasets, which would violate

our

privacy policy.

Since files with the same extension have similar properties and

requirements,

some file system management policies

can be improved by including special-case treatment for particular

extensions.

Such special-case treatment can be built into the file system or

autonomically

and dynamically learned [16].

Since nearly half the files, and

nearly half the bytes, belong to files with a few popular extensions,

developing such special-case treatment for only a few particular

extensions

can optimize performance for a large fraction of the file system.

Furthermore, since the same extensions continue to be popular year

after year,

one can develop special-case treatments for today's popular extensions

and

expect that they will still be useful years from now.

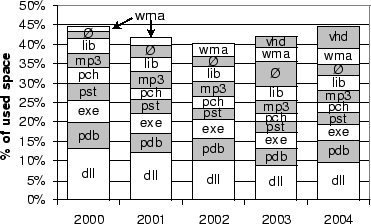

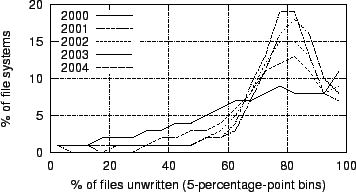

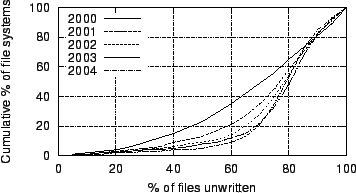

Figure 11:

Histograms of file systems by percentage of files unwritten

|

Figure 12:

CDFs of file systems by percentage of files unwritten

|

Figures 11

and 12

plot histograms and CDFs,

respectively, of file systems by percentage of files that have not been

written since they were copied onto the file system. We identify such

files

as ones whose modification timestamps are earlier than their creation

timestamps, since the creation timestamp of a copied file is set to the

time

at which the copy was made, but its modification timestamp is copied

from the

original file. Over our sample period, the arithmetic mean of the

percentage

of locally unwritten files has grown from 66% to 76%, and the median

has

grown from 70% to 78%. This suggests that users locally contribute to a

decreasing fraction of their systems' content. This may in part be due

to the

increasing amount of total content over time.

Since more and more files are being copied across file systems

rather than

generated locally, we can expect identifying and coalescing identical

copies

to become increasingly important in systems that aggregate file

systems.

Examples of systems with such support are the FARSITE distributed file

system [1], the Pastiche

peer-to-peer backup system [8],

and the Single Instance Store in Windows file servers [5].

4 Directories

4.1 Directory count per file system

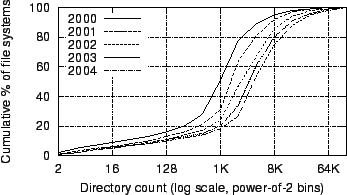

Figure 13:

CDFs of file systems by directory count

|

Figure 13

plots CDFs of file

systems by count of directories. The count of directories per file

system has

increased steadily over our five-year sample period: The arithmetic

mean has

grown from 2400 to 8900 directories and the median has grown from 1K to

4K

directories.

We discussed implications of the rising number of directories per

file system

earlier, in §3.1.

This section describes our findings regarding directory size, measured

by

count of contained files, count of contained subdirectories, and total

entry

count. None of these size distributions has changed appreciably over

our

sample period, but the mean count of files per directory has decreased

slightly.

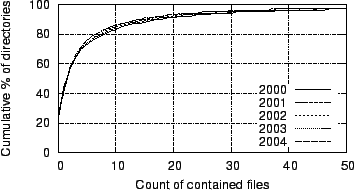

Figure 14:

CDFs of directories by file

count

|

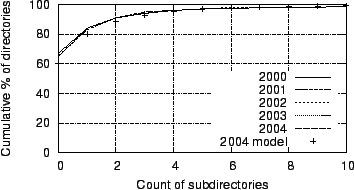

Figure 15:

CDFs of directories by subdirectory

count

|

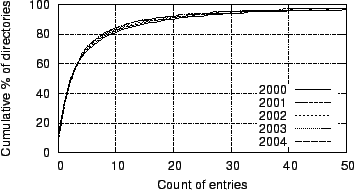

Figure 16:

CDFs of directories by entry

count

|

Figure 14

plots CDFs of directories

by size, as measured by count of files in the directory. It shows that

although the absolute count of directories per file system has grown

significantly over time, the distribution has not changed appreciably.

Across

all years, 23-25% of directories contain no files, which marks a change

from

1998, in which only 18% contained no files and there were more

directories

containing one file than those containing none. The arithmetic mean

directory

size has decreased slightly and steadily from 12.5 to 10.2 over the

sample

period, but the median directory size has remained steady at

2 files.

Figure 15

plots CDFs of

directories by size, as measured by count of subdirectories in the

directory.

It includes a model approximation we will discuss later in

§4.5. This distribution

has remained unchanged

over our sample period. Across all years, 65-67% of directories contain

no

subdirectories, which is similar to the 69% found in 1998.

Figure 16

plots CDFs of directories

by size, as measured by count of total entries in the directory. This

distribution has remained largely unchanged over our sample period.

Across

all years, 46-49% of directories contain two or fewer entries.

Since there are so many directories with a small number of files, it

would not

take much space to colocate the metadata for most of those files with

those

directories. Such a layout would reduce seeks associated with file

accesses.

Therefore, it might be useful to preallocate a small amount of space

near a

new directory to hold a modest amount of child metadata. Similarly,

most

directories contain fewer than twenty entries, suggesting using an

on-disk

structure for directories that optimizes for this common case.

4.3 Special directories

This section describes our findings regarding the usage of Windows

special

directories. We find that an increasing fraction of file-system storage

is in

the namespace subtree devoted to system files, and the same holds for

the

subtree devoted to user documents and settings.

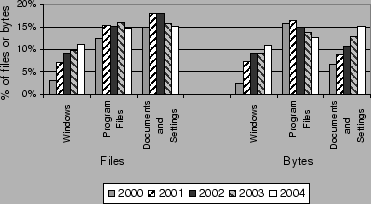

Figure 17:

Fraction of files and bytes in special

subtrees

|

Figure 17

plots the fraction of

file-system files that reside within subtrees rooted in each of three

special

directories: Windows, Program Files, and Documents

and Settings. This figure also plots the fraction of file-system

bytes

contained within each of these special subtrees.

For the Windows subtree, the fractions of files and bytes

have both

risen from 2-3% to 11% over our sample period, suggesting that an

increasingly large fraction of file-system storage is devoted to system

files.

In particular, we note that Windows XP was released between the

times of our

2000 and 2001 data collections.

For the Program Files subtree, the fractions of files and

bytes have

trended in opposite directions within the range of 12-16%. For the

Documents and Settings subtree, the fraction of bytes has

increased

dramatically while the fraction of files has remained relatively

stable.

The fraction of all files accounted for by these subtrees has risen

from 25%

to 40%, and the fraction of bytes therein has risen from 30% to 41%,

suggesting that application writers and end users have increasingly

adopted

Windows' prescriptive namespace organization [7].

Backup software generally does not have to back up system files,

since they

are static and easily restored. Since system files are accounting for a

larger and larger fraction of used space, it is becoming more and more

useful

for backup software to exclude these files.

On the other hand, files in the Documents and Settings folder tend

to be the

most important files to back up, since they contain user-generated

content and

configuration information. Since the percentage of bytes devoted to

these

files is increasing, backup capacity planners should expect,

surprisingly,

that their capacity requirements will increase faster than disk

capacity is planned to grow. On the other hand, the percentage of files

is

not increasing, so they need not expect metadata storage requirements

to scale

faster than disk capacity. This may be relevant if metadata is backed

up in a

separate repository from the data, as done by systems such as EMC

Centera [13].

4.4 Namespace tree depth

This section describes our findings regarding the depth of directories,

files,

and bytes in the namespace tree. We find that there are many files deep

in

the namespace tree, especially at depth 7. Also, we find that files

deeper in

the namespace tree tend to be orders-of-magnitude smaller than

shallower

files.

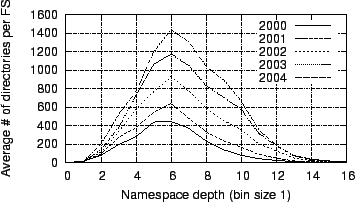

Figure 18:

Histograms of directories by namespace

depth

|

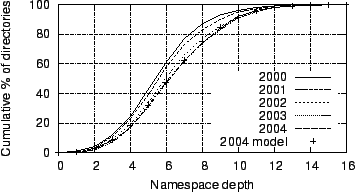

Figure 19:

CDFs of directories by namespace

depth

|

Figure 18

plots histograms

of directories by their depth in the namespace tree, and

Figure 19

plots CDFs of this

same data; it also includes a model approximation we will discuss later

in

§4.5. The general shape

of the distribution has

remained consistent over our sample period, but the arithmetic mean has

grown

from 6.1 to 6.9, and the median directory depth has increased from 5 to

6.

Figure 20:

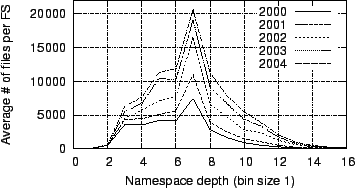

Histograms of files by namespace

depth

|

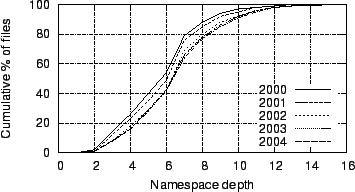

Figure 21:

CDFs of files by namespace

depth

|

Figure 20

plots histograms of

file count by depth in the namespace tree, and

Figure 21

plots CDFs of this same

data. With a few exceptions, such as at depths 2, 3, and 7, these

distributions roughly track the observed distributions of directory

depth,

indicating that the count of files per directory is mostly independent

of

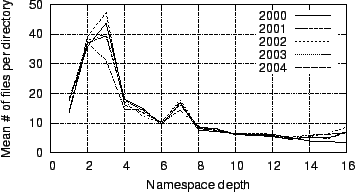

directory depth. To study this more directly,

Figure 22

plots the mean count

of files per directory versus directory depth. There is a slight

downward

trend in this ratio with increasing depth, punctuated by three depths

whose

directories have greater-than-typical counts of files: At depth 2 are

files in

the Windows and Program Files directories; at depth

3 are

files in the System and System32 directories; and

at depth 7

are files in the web cache directories.

Figure 22:

Files per directory vs. namespace depth

|

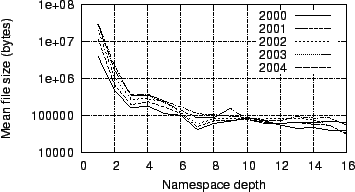

Figure 23:

File size vs. namespace depth

|

Figure 23 plots

the mean file size versus

directory depth on a logarithmic scale. We see here that files deeper

in the

namespace tree tend to be smaller than shallower ones. The mean file

size

drops by two orders of magnitude between depth 1 and depth 3,

and there is a

drop of roughly 10% per depth level thereafter. This phenomenon occurs

because most bytes are concentrated in a small number of large files

(see

Figures 2

and 4),

and these files

tend to reside in shallow levels of the namespace tree. In particular,

the

hibernation image file is located in the root.

Since many files and directories are deep in the namespace tree,

efficient

path lookup of deep paths should be a priority for file system

designers. For

instance, in distributed file systems where different servers are

responsible

for different parts of the namespace tree [1], deep path lookup may

be expensive if not optimized. The high depth of many entries in the

namespace may also be of interest to designers of file system

visualization

GUIs, to determine how much column space to allot for directory

traversal.

Furthermore, since the fraction of files at high depths is increasing

across

the years of our study, these lessons will become more and more

important as

years pass.

The clear trend of decreasing file size with increasing namespace

tree depth

sugests a simple coarse mechanism to predict future file size at time

of file

creation. File systems might use such prediction to decide where on

disk to

place a new file.

4.5 Namespace depth model

We have developed a generative model that accounts for the distribution

of

directory depth. The model posits that new subdirectories are created

inside

an existing directory in offset proportion to the count of

subdirectories

already in that directory.

In our previous study [9],

we observed that the distribution of

directories by depth could be approximated by a Poisson distribution

with

, yielding a maximum displacement of cumulative curves

(MDCC)

of 2%. Poisson is also an acceptable approximation for the five

datasets in

the present study, with , yielding a maximum displacement of cumulative curves

(MDCC)

of 2%. Poisson is also an acceptable approximation for the five

datasets in

the present study, with  growing from 6.03 to

6.88 over the sample

period, yielding MDCCs that range from 1% to 4%. However, the Poisson

distribution does not provide an explanation for the behavior; it

merely

provides a means to approximate the result. By contrast, we have

developed a

generative model that accounts for the distribution of directory depths

we

have observed, with accuracy comparable to the Poisson model. growing from 6.03 to

6.88 over the sample

period, yielding MDCCs that range from 1% to 4%. However, the Poisson

distribution does not provide an explanation for the behavior; it

merely

provides a means to approximate the result. By contrast, we have

developed a

generative model that accounts for the distribution of directory depths

we

have observed, with accuracy comparable to the Poisson model.

The generative model is as follows. A file system begins with an

empty root

directory. Directories are added to the file system one at a time. For

each

new directory, a parent directory is selected probabilistically, based

on the

count of subdirectories the parent currently has. Specifically, the

probability of choosing each extant directory as a parent is

proportional to

, where , where  is the count of

extant subdirectories of directory is the count of

extant subdirectories of directory

. We used Monte Carlo simulation to compute directory depth

distributions

according to this generative model. Given a count of directories in a

file

system, the model produces a distribution of directory depths that

matches the

observed distribution for file systems of that size.

Figure 19

plots the aggregate

result of the model for all file systems in the 2004 dataset. The model

closely matches the CDF of observed directory depths, with an MDCC of

1%. . We used Monte Carlo simulation to compute directory depth

distributions

according to this generative model. Given a count of directories in a

file

system, the model produces a distribution of directory depths that

matches the

observed distribution for file systems of that size.

Figure 19

plots the aggregate

result of the model for all file systems in the 2004 dataset. The model

closely matches the CDF of observed directory depths, with an MDCC of

1%.

Our generative model accounts not only for the distribution of

directory depth

but also for that of subdirectory size.

Figure 15

shows this for the

2004 dataset. The model closely matches the CDF, with an MDCC of 5%.

Intuitively, the proportional probability  can be interpreted as

follows: If a directory already has some subdirectories, it has

demonstrated

that it is a useful location for subdirectories, and so it is a likely

place

for more subdirectories to be created. The more subdirectories it has,

the

more demonstrably useful it has been as a subdirectory home, so the

more

likely it is to continue to spawn new subdirectories. If the

probability were

proportional to

can be interpreted as

follows: If a directory already has some subdirectories, it has

demonstrated

that it is a useful location for subdirectories, and so it is a likely

place

for more subdirectories to be created. The more subdirectories it has,

the

more demonstrably useful it has been as a subdirectory home, so the

more

likely it is to continue to spawn new subdirectories. If the

probability were

proportional to  without any offset, then an empty

directory could never

become non-empty, so some offset is necessary. We found an offset of 2

to

match our observed distributions very closely for all five years of our

collected data, but we do not understand why the particular value of 2

should

be appropriate. without any offset, then an empty

directory could never

become non-empty, so some offset is necessary. We found an offset of 2

to

match our observed distributions very closely for all five years of our

collected data, but we do not understand why the particular value of 2

should

be appropriate.

5 Space Usage

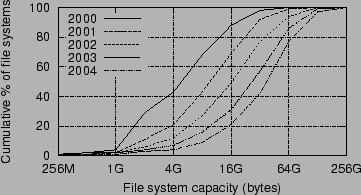

Figure 24:

CDFs of file systems by storage capacity

|

Figure 24

plots CDFs of file

system volumes by storage capacity, which has increased dramatically

over our

five-year sample period: The arithmetic mean has grown from 8 GB

to 46 GB and

the median has grown from 5 GB to 40 GB. The number of

small-capacity file

system volumes has dropped dramatically: Systems of 4 GB or less

have gone

from 43% to 4% of all file systems.

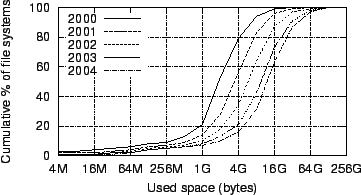

Figure 25:

CDFs of file systems by total consumed space

|

Figure 25

plots CDFs of

file systems by total consumed space, including not only file content

but also

space consumed by internal fragmentation, file metadata, and the system

paging

file. Space consumption increased steadily over our five-year sample

period:

The geometric mean has grown from 1 GB to 9 GB, the

arithmetic mean has grown

from 3 GB to 18 GB, and the median has grown from 2 GB

to 13 GB.

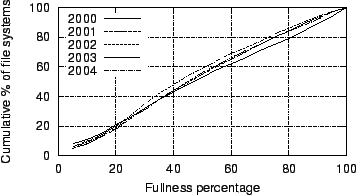

Figure 26:

CDFs of file systems by fullness

|

Figure 26

plots CDFs of file systems

by percentage of fullness, meaning the consumed space relative to

capacity.

The distribution is very nearly uniform for all years, as it was in our

1998

study. The mean fullness has dropped slightly from 49% to 45%, and the

median file system has gone from 47% full to 42% full. By contrast, the

aggregate fullness of our sample population, computed as total consumed

space

divided by total file-system capacity, has held steady at 41% over all

years.

In any given year, the range of file system capacities in this

organization is

quite large. This means that software must be able to accommodate a

wide

range of capacities simultaneously existing within an organization. For

instance, a peer-to-peer backup system must be aware that some machines

will

have drastically more capacity than others. File system designs, which

must

last many years, must accommodate even more dramatic capacity

differentials.

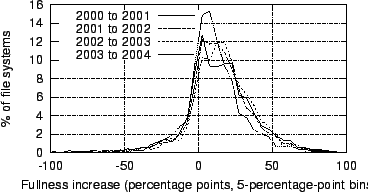

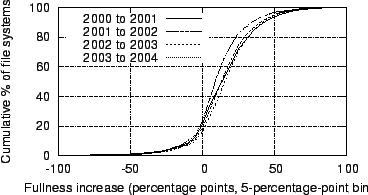

5.2 Changes in usage

This subsection describes our findings regarding how individual file

systems

change in fullness over time. For this part of our work, we examined

the 6536

snapshot pairs that correspond to the same file system in two

consecutive

years. We also examined the 1320 snapshot pairs that correspond to the

same

file system two years apart. We find that 80% of file systems become

fuller

over a one-year period, and the mean increase in fullness is 14

percentage

points. This increase is predominantly due to creation of new files,

partly

offset by deletion of old files, rather than due to extant files

changing

size.

When comparing two matching snapshots in different years, we must

establish

whether two files in successive snapshots of the same file system are

the same

file. We do not have access to files' inode numbers, because collecting

them

would have lengthened our scan times to an unacceptable degree. We thus

instead use the following proxy for file sameness: If the files have

the same

full pathname, they are considered the same, otherwise they are not.

This is

a conservative approach: It will judge a file to be two distinct files

if it

or any ancestor directory has been renamed.

Figure 27:

Histograms of file systems by 1-year fullness increase

|

Figure 28:

CDFs of file systems by 1-year fullness increase

|

Figures 27

and 28

plot histograms and

CDFs, respectively, of file systems by percentage-point increase in

fullness

from one year to the next. We define this term by example: If a file

system

was 50% full in 2000 and 60% full in 2001, it exhibited a 10

percentage-point increase in fullness. The distribution is

substantially the

same for all four pairs of consecutive years.

Figure 28

shows that

80% of file systems exhibit an increase in fullness and fewer than 20%

exhibit a decrease. The mean increase from one year to the next is 14

percentage points.

We also examined the increase in fullness over two years. We found

the mean

increase to be 22 percentage points. This is less than twice the

consecutive-year increase, indicating that as file systems age, they

increase

their fullness at a slower rate. Because we have so few file systems

with

snapshots in four consecutive years, we did not explore increases over

three

or more years.

Since file systems that persist for a year tend to increase their

fullness by

about 14 points, but the mean file-system fullness has dropped from 49%

to

45% over our sample period, it seems that the steadily increasing

fullness of

individual file systems is offset by the replacement of old file

systems with

newer, emptier ones.

Analyzing the factors that contribute to the 14-point mean

year-to-year

increase in fullness revealed the following breakdown: Fullness

increases by

28 percentage points due to files that are present in the later

snapshot but

not in the earlier one, meaning that they were created during the

intervening

year. Fullness decreases by 15 percentage points due to files that are

present in the earlier snapshot but not in the later one, meaning that

they

were deleted during the intervening year. Fullness also increases by 1

percentage point due to growth in the size of files that are present in

both

snapshots. An insignificant fraction of this increase is attributable

to

changes in system paging files, internal fragmentation, or metadata

storage.

We examined the size distributions of files that were created and of

files

that were deleted, to see if they differed from the overall file-size

distribution. We found that they do not differ appreciably. We had

hypothesized that users tend to delete large files to make room for new

content, but the evidence does not support this hypothesis.

Since deleted files and created files have similar size

distributions, file

system designers need not expect the fraction of files of different

sizes to

change as a file system ages. Thus, if they find it useful to assign

different parts of the disk to files of different sizes, they can

anticipate

the allocation of sizes to disk areas to not need radical change as

time

passes.

Many peer-to-peer systems use free space on computers to store

shared data, so

the amount of used space is of great importance. With an understanding

of how

this free space decreases as a file system ages, a peer-to-peer system

can

proactively plan how much it will need to offload shared data from each

file

system to make room for additional local content. Also, since a common

reason

for upgrading a computer is because its disk space becomes exhausted, a

peer-to-peer system can use a prediction of when a file system will

become

full as a coarse approximation to when that file system will become

unavailable.

6 Related Work

This research extends our earlier work in measuring and modeling

file-system

metadata on Windows workstations. In 1998, we collected snapshots of

over ten

thousand file systems on the desktop computers at Microsoft [9].

The focus of the earlier study was on variations among

file systems within the sample, all of which were captured at the same

time.

By contrast, the focus of the present study is on longitudinal

analysis,

meaning how file systems have changed over time.

Prior to our previous study, there were no studies of static

file-system

metadata on Windows systems, but there were several such studies in

other

operating-system environments. These include Satyanarayanan's study of

a

Digital PDP-10 at CMU in 1981 [24],

Mullender and Tanenbaum's study

of a Unix system at Vrije Universiteit in 1984 [20], Irlam's

study of 1050 Unix file systems in 1993 [14], and Sienknecht et

al.'s study of 267 file systems in 46 HP-UX systems at Hewlett-Packard

in

1994 [25]. All of these

studies involved snapshots taken at a

single time, like our study in 1998. There have also been longitudinal

studies of file-system metadata, but for significantly shorter times

than

ours: Bennett et al. studied three file servers at the

University of Western

Ontario over a period of one day in 1991 [4], and Smith and

Seltzer studied 48 file systems on four file servers at Harvard over a

period

of ten months in 1994 [26].

We are aware of only one additional collection of static file-system

metadata

since our previous study. In 2001, Evans and Kuenning captured

snapshots from

22 machines running various operating systems at Harvey Mudd College

and

Marine Biological Laboratories [11].

Their data collection and

analysis focused mainly, but not exclusively, on media files. Their

findings

show that different types of files exhibit significantly different size

distributions, which our results support.

Many studies have examined dynamic file-system traces rather than

static file

system snapshots. These studies are complementary to ours, describing

things

we cannot analyze such as the rate at which bytes are read and written

in a

file system. A few examples of such studies are Ousterhout et al. 's

analysis

of the BSD file system [21],

Gribble et al. 's analysis of

self-similarity in the dynamic behavior of various file

systems [12], Vogels's

analysis of Windows NT [28],

and

Roselli et al. 's analysis of HP-UX and Windows NT [23].

In addition to file-system measurement research, there has been much

work in

modeling file-system characteristics, most notably related to the

distribution

of file sizes. Examples of work in this area include that of

Satyanarayanan [24], Barford

and Crovella [3],

Downey [10], and

Mitzenmacher [19].

In 2001, Evans and Kuenning broke down measured file-size

distributions

according to file type, and they modeled the sizes using log-lambda

distributions [11]. They found

that video and audio files can

significantly perturb the file-size distribution and prevent simple

size

models from applying. We did not find this to be true for file sizes in

our

sample population. However, we did find video, database, and blob files

responsible for a second peak in the distribution of bytes by

containing file

size.

In our previous study, we modeled directory depth with a Poisson

distribution [9], but we have

herein proposed a generative model in

which the attractiveness of an extant directory  as a

location for a new

subdirectory is proportional to as a

location for a new

subdirectory is proportional to  , where , where  is the count of

directory is the count of

directory  's extant subdirectories. This is strikingly

similar to the rule

for generating plane-oriented recursive trees, wherein the probability

is

proportional to 's extant subdirectories. This is strikingly

similar to the rule

for generating plane-oriented recursive trees, wherein the probability

is

proportional to  [15]. [15].

7 Summary and Conclusions

Over a span of five years, we collected metadata snapshots from more

than

63,000 distinct Windows file systems in a commercial environment,

through

voluntary participation of the systems' users. These systems contain 4

billion files totaling 700 TB of file data. For more than 10% of

these file

systems, we obtained snapshots in multiple years, enabling us to

directly

observe how these file systems have changed over time. Our measurements

reveal several interesting properties of file systems and offer useful

lessons.

One interesting discovery is the emergence of a second mode in the

GB

range in the distribution of bytes by containing file size. It makes us

wonder if at some future time a third mode will arise. The increasingly

large fraction of content in large files suggests that variable block

sizes, as supported by ZFS [6]

and NTFS [27],

are becoming increasingly important. Since a few large files, mainly

video, database, and blob files, are contributing to an increasing

fraction of file-system usage, these file extensions are ideal

candidates for larger block sizes.

Although large files account for a large fraction of space, most

files

are 4 KB or smaller. Thus, it is useful to colocate several small

files

in a single block, as ReiserFS [22]

does, and to colocate

small file content with file metadata, as NTFS does. Our finding that

most directories have few entries suggests yet another possibility:

Colocate small file content with the file's parent directory. An even

more extreme solution is suggested by the fact that in 2004, the

average

file system had only 52 MB in files 4 KB or smaller. Since

this number

is becoming small relative to main memory sizes, it may soon be

practical to avoid cache misses entirely for small files by prefetching

them all at boot time and pinning them in the cache.

Another noteworthy discovery is that the fraction of files locally

modified decreases with time, an effect significant enough to be

observable in only a five-year sample. It would appear that users'

ability to generate increasing amounts of content is outstripped by the

phenomenal growth in their disks. If individuals copying content from

each other becomes increasingly common, then applications like

peer-to-peer backup will have increasing amounts of inter-machine

content similarity to leverage to obviate copying.

We were surprised to find a strong negative correlation between

namespace depth and file size. Such a strong and temporally-invariant

correlation, in combination with the well-known correlation between

file

extension and file size, can help us make predictions of file size at

creation time. This may be useful, e.g., to decide how many blocks to

initially allocate to a file.

We also discovered that a simple generative model can account for

both

the distributions of directory depth and the count of subdirectories

per

directory. The model we developed posits that new subdirectories are

created inside an existing directory in offset proportion to the count

of subdirectories already in that directory. This behavior is easy to

simulate, and it produces directory-depth and directory-size

distributions that closely match our observations.

Finally, it is remarkable that file system fullness over the course

of

five years has changed little despite the vast increase in file system

capacity over that same period. It seems clear that users scale their

capacity needs to their available capacity. The lesson for storage

manufacturers is to keep focusing effort on increasing capacity,

because

customers will continue to place great value on capacity for the

foreseeable future.

The authors would like to express great thanks to the many Microsoft

users who

consented to us taking snapshots of their file systems. Without them,

this

study would have been impossible. We also thank Jim Gray, Catharine van

Ingen, and Tim Harris for their comments on early drafts of this paper.

Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewers and our shepherd, Randal

Burns, for

their many helpful comments and suggestions.

-

- 1

- ADYA, A., BOLOSKY, W., CASTRO,

M., CERMAK, G., CHAIKEN, R.,

DOUCEUR, J., HOWELL, J., LORCH, J.,

THEIMER, M., AND WATTENHOFER, R. P.

FARSITE: Federated, available, and reliable storage for an incompletely

trusted environment.

In Proceedings of the Fifth USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems

Design and Implementation (OSDI) (Boston, MA, December 2002),

pp. 1-14.

- 2

- ARPACI-DUSSEAU, A. C., AND

ARPACI-DUSSEAU, R. H.

Information and control in gray-box systems.

In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems

Principles (SOSP) (Banff, Canada, October 2001), pp. 43-56.

- 3

- BARFORD, P., AND CROVELLA,

M.

Generating representative web workloads for network and server

performance evaluation.

In Proceedings of the 1998 Joint International Conference on

Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems (SIGMETRICS)

(Madison, WI, June 1998), pp. 151-160.

- 4

- BENNETT, J. M., BAUER, M. A.,

AND KINCHLEA, D.

Characteristics of files in NFS environments.

In Proceedings of the 1991 ACM SIGSMALL/PC Symposium on Small

Systems (Toronto, Ontario, June 1991), pp. 33-40.

- 5

- BOLOSKY, W. J., CORBIN, S., GOEBEL,

D., AND DOUCEUR, J. R.

Single instance storage in Windows 2000.

In Proceedings of the 4th USENIX Windows Systems Symposium

(Seattle, WA, August 2000).

- 6

- BONWICK, J.

Zfs: The last word in file systems.

Available at https://www.opensolaris.org/os/

community/zfs/docs/zfs_last.pdf.

- 7

- CHAPMAN, G.

Why does Explorer think I only want to see my documents?

Available at https://pubs.logicalexpressions.com/

Pub0009/LPMArticle.asp?ID=189.

- 8

- COX, L. P., MURRAY, C. D.,

AND NOBLE, B. D.

Pastiche: Making backup cheap and easy.

In Proceedings of the Fifth USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems

Design and Implementation (OSDI) (Boston, MA, December 2002),

pp. 285-298.

- 9

- DOUCEUR, J. R., AND BOLOSKY,

W. J.

A large-scale study of file-system contents.

In Proceedings of the 1999 Joint International Conference on

Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems (SIGMETRICS)

(Atlanta, GA, May 1999), pp. 59-70.

- 10

- DOWNEY, A. B.

The structural cause of file size distributions.

In Proceedings of the 2001 Joint International Conference on

Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems (SIGMETRICS)

(Cambridge, MA, June 2001), pp. 328-329.

- 11

- EVANS, K. M., AND KUENNING,

G. H.

A study of irregularities in file-size distributions.

In Proceedings of the 2002 International Symposium on Performance

Evaluation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (SPECTS) (San

Diego, CA, July 2002).

- 12

- GRIBBLE, S. D., MANKU, G. S.,

ROSELLI, D. S., BREWER, E. A.,

GIBSON, T. J., AND MILLER,

E. L.

Self-similarity in file systems.

In Proceedings of the 1998 Joint International Conference on

Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems (SIGMETRICS)

(Madison, WI, June 1998), pp. 141-150.

- 13

- GUNAWI, H. S., AGRAWAL, N., ARPACI-DUSSEAU,

A. C., ARPACI-DUSSEAU, R. H.,

AND SCHINDLER, J.

Deconstructing commodity storage clusters.

In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Computer

Architecture (ISCA) (Madison, WI, June 2005), pp. 60-71.

- 14

- IRLAM, G.

Unix file size survey - 1993.

Available at https://www.base.com/gordoni/ufs93.html.

- 15

- MAHMOUD, H. M.

Distances in random plane-oriented recursive trees.

Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 41

(1992), 237-245.

- 16

- MESNIER, M., THERESKA, E., GANGER,

G. R., ELLARD, D., AND SELTZER,

M.

File classification in self-* storage systems.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Autonomic

Computing (ICAC) (New York, NY, May 2004).

- 17

- MICROSOFT.

SetFileTime.

Available at MSDN, https://msdn.microsoft.com/library/

default.asp?url=/library/en-us/wcecoreos5/html/

wce50lrfsetfiletime.asp.

- 18

- MITCHELL, S.

Inside the Windows 95 file system.

O'Reilly and Associates, 1997.

- 19

- MITZENMACHER, M.

Dynamic models for file sizes and double Pareto distributions.

Internet Mathematics 1, 3 (2004), 305-333.

- 20

- MULLENDER, S. J., AND TANENBAUM,

A. S.

Immediate files.

Software--Practice and Experience 14, 4 (April 1984),

365-368.

- 21

- OUSTERHOUT, J. K., COSTA, H. D.,

HARRISON, D., KUNZE, J. A., KUPFER,

M., AND THOMPSON, J. G.

A trace-driven analysis of the UNIX 4.2 BSD file system.

In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems

Principles (SOSP) (Orcas Island, WA, December 1985),

pp. 15-24.

- 22

- REISER, H.

Three reasons why ReiserFS is great for you.

Available at https://www.namesys.com/.

- 23

- ROSELLI, D., LORCH, J. R., AND

ANDERSON, T. E.

A comparison of file system workloads.

In Proceedings of the 2000 USENIX Annual Technical Conference

(San Diego, CA, June 2000), pp. 41-54.

- 24

- SATYANARAYANAN, M.

A study of file sizes and functional lifetimes.

In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems

Principles (SOSP) (Pacific Grove, CA, December 1981),

pp. 96-108.

- 25

- SIENKNECHT, T. F., FRIEDRICH, R. J.,

MARTINKA, J. J., AND FRIEDENBACH,

P. M.

The implications of distributed data in a commercial environment on the

design of hierarchical storage management.

Performance Evaluation 20, 1-3 (May 1994), 3-25.

- 26

- SMITH, K., AND SELTZER, M.

File layout and file system performance.

Technical Report TR-35-94, Harvard University, 1994.

- 27

- SOLOMON, D. A.

Inside Windows NT, 2nd ed.

Microsoft Press, 1998.

- 28

- VOGELS, W.

File system usage in Windows NT 4.0.

In Proceedings of the 17th ACM Symposium on Operating Systems

Principles (SOSP) (Kiawah Island, SC, December 1999),

pp. 93-109.

A Five-Year Study

of File-System Metadata

This document was generated using the

LaTeX2HTML

translator Version 2002-2-1 (1.70)

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos Drakos,

Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross Moore,

Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -split 0 -show_section_numbers

-local_icons fsstudy.tex

The translation was initiated by Nitin Agrawal on 2006-12-18

Nitin Agrawal

2006-12-18

|